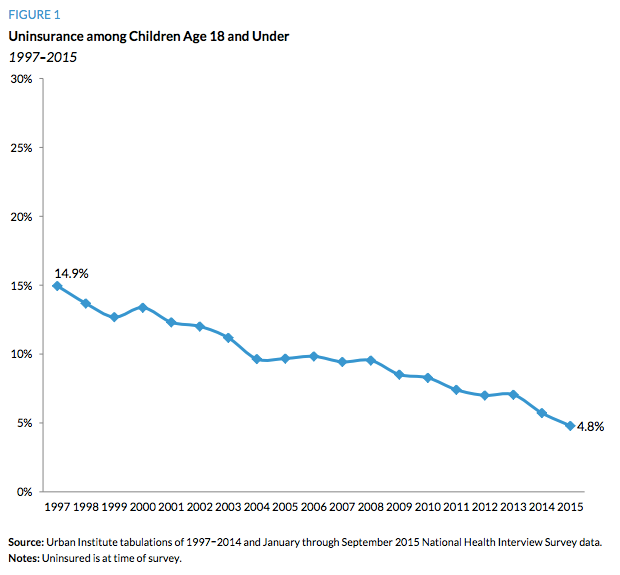

Medicaid, in partnership with the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), has led the way in helping to cut the nation’s uninsured rate dramatically. This has been a long journey in which the percentage of uninsured children has dropped from 14.9 percent in 1997 to just 4.8 percent in 2015 — a 68 percent reduction. That is the definition of success.

Consequently, both President-elect Donald Trump and the Congress should ensure that they “do no harm” and not reverse the incredible progress that has been made.

Unfortunately, the dreadful idea of block granting the Medicaid program is being proposed, once again. It would be terrible public policy, but somehow, it just won’t seem to die. In fact, we have seen this zombie idea before — time and time again (in 1981, 1995, 1996, 2003, and 2005).

But unlike mythical creatures that are really harmless, Medicaid block grants pose an enormous threat to the health and well-being of millions of our nation’s must vulnerable citizens and to our doctors, nurses, hospitals, clinics, and other health care professionals that make up our nation’s health care system. This is why the concept has been repeatedly defeated on a bipartisan basis.

Setting Off the Funding Formula Fight of the Century

Here’s how it would “work”: the federal government would arbitrarily decide in 2017 just how much it would spend on Medicaid for the next 10 years or even decades into the future. States would be allocated a share of those dollars based on an allocation formula that is purely political.

This would create the block grant formula fight of the century. The House and Senate would revert to a political Lord of the Flies, as billions and billions of dollars would be at stake.

States with historically high costs will argue the cost of living in their states are higher so their higher funding levels should be maintained. States with lower costs will argue they should not be punished for having run more cost-effective programs. States with rapidly growing populations will argue that any and all growth in funding should be dedicated to them. Likewise, states with static or declining populations will fight vehemently against flat funding or reductions over time because that would make them a “loser state.” It will be a battle of whose magnitude Congress has never seen before.

The importance of this fight for each and every state cannot be underestimated. During consideration of the welfare reform bill in 1996, which converted Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) to a block grant called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the legislation lay dormant for months while House and Senate members went to war. The fight was brutal over whether states would simply get the amount they historically spent or whether the funding would be distributed more equitable on a “per child in poverty” basis.

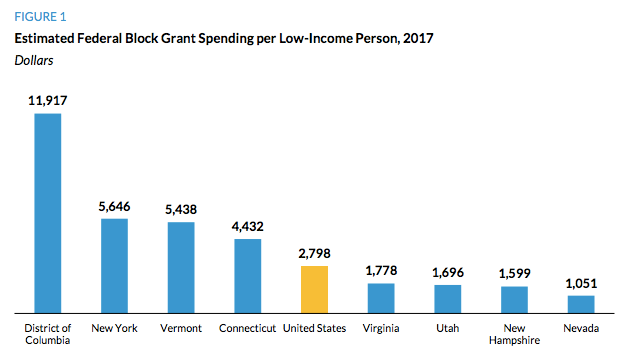

Historical spending levels won over “fairness.” Ironically, a Republican Congress rewarded the more “liberal” states in this instead and failed to take into account factors such as economic downturns, population changes, etc. Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Utah lost the formula fight in 1996 and the disparity in funding has only increased for them under the block grant because of changes in population and child poverty rates between the states over time.

For example, Connecticut received an astounding 6.11 times more funding per child in poverty than Texas in 1997 ($2,200 to $360), and the block grant increased that disparity to 9.50 times ($2,792 to $294) by 2009. Nobody can possibly defend a block grant formula that gives Connecticut 850 percent more funding per child in poverty than Texas.

This disparity in funding highlights one of the major problems with block grants, as unfair funding formulas are created and are unable to adjust to need. Thus, in 2011, it might be no surprise that Connecticut had a child poverty rate of 15 percent while Texas had a child poverty rate of 27 percent. As Texas’s population and child poverty numbers grew, federal funding remained static. Therefore, Texas and similarly situated states have had less federal support to address a growing problem.

While AFDC lifted 2.2 million children out of poverty in 1995, TANF’s block grant helped lift just 629,000 children out of poverty in 2010, according to an analysis by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Similar disparities and harm would plague Medicaid if it were converted into a block grant.

Shattering the Health System and Coverage Across the Country

Why would we want TANF as a model for Medicaid reform? Such a financing structure would be an outright disaster for the American health care system and the millions of Americans that Medicaid serves. States would be stupid to be hoodwinked by the federal government into accepting the elixir of “state flexibility” in exchange for billions of dollars in federal budget cuts.

First, block grants allow federal lawmakers to bear no responsibility or to provide any assistance with changes in need, such as recessions, natural disaster, or demographic variations that occur over time.

Second, since block grant allocations are arbitrary, this funding becomes an easy target for Congress to raid when they want to fund a different pet project. The states should understand the burden of any cut or shortfall in funding falls entirely on them.

Thus, low-income senior citizens, people with disabilities, and children, and health care providers, and the states must fully comprehend that House Budget Committee Chairman Tom Price’s proposed budget would have block granted and cut Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) by an astounding $913 billion over the next decade.

States would be forced to use their newfound “state flexibility” to confront a number of disturbing choices, such as cutting children, pregnant women, people with disabilities, or low-income senior citizens off of coverage, imposing enrollment freezes (disproportionately harming babies), putting those in need on waiting lists, withhold certain medical benefits, slashing payment rates to providers, raising taxes, or most likely, all of the above.

Compounding the problem, while Medicaid currently automatically adjusts for growing need, block grants do not. Thus, states going through a recession, population growth, or a natural disaster would face even more disturbing choices. States would be forced to cut back on care precisely when people are hurting the most and the economy needs a boost and not countercyclical cuts in support.

The fact is that you cannot cut $913 billion out of Medicaid and not expect infant and children, pregnant women, people with disability, and senior citizens not to be harmed.

Imposing Harm Upon Vulnerable Populations, Particularly Children

The first to feel the brunt of such cuts are typically the least politically powerful. Consequently, the biggest losers in a world of Medicaid block grants and government rationing would likely be children. As Republican Senator John Chafee said in opposition to such a proposal back in 1996:

As states are forced to ration finite resources under a block grant, governors and legislators would be forced to choose among three very compelling groups of beneficiaries.

Who are they? Children, the elderly, and the disabled. They are the groups that primarily they would have to choose amongst. Unfortunately, I suspect that children would be the ones that would lose out.

For a number of reasons, Medicaid block grants would be disastrous for child health, and this is not theoretical. In fact, we don’t have to go far to see how this would work in practice because the federal government already gives Puerto Rico and the territories a Medicaid block grant and the Indian Health Service (IHS) operates under an annually capped appropriation — much like a block grant.

So, how is that working out for children in Puerto Rico and Native Americans covered by IHS?

Learning the Lessons from Puerto Rico’s Medicaid Block Grants

In Puerto Rico, the federal government imposes a Medicaid block grant upon the Commonwealth to help support its “Mi Salud” program. Since block grants are arbitrary and fail to adjust for need, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) has found that, prior to the receipt of additional federal support through the enactment of the Affordable Care Act (ACA):

. . .federal Medicaid funds covered only 16 percent of their planned annual expenditures and were expended during the first quarter of the federal fiscal year, after which time the territory had to rely entirely on local funding to cover program spending.

In the 50 states and the District of Columbia, Medicaid spending adjusts for need, but not under a block grant. As David Thomsen of the National Council of La Raza points out, Puerto Rico has nearly the same population as Oklahoma and far greater poverty, but only receive one-tenth of the support from Medicaid that Oklahoma does.

In February of this year, First Focus wrote a letter to the House Energy and Commerce Committee about the perils of the Medicaid block grant on Puerto Rico. We pointed out:

The effects on Puerto Rico’s children have been devastating. Doctors are fleeing to the mainland or refusing to accept patients on Medicaid, leaving children without access to pediatric and preventive care. Consequently, children are more likely to have preventable hospitalizations and use overwhelmed hospital emergency departments for illnesses that should be treated by primary care physicians. Furthermore, the lack of access to specialists leaves children at risk of developing preventable chronic diseases.

The Medicaid block grant is doing incredible harm to Puerto Rico’s entire health system and is a major factor in the Commonwealth’s debt crisis. According to Dr. Johnny Rullán, Puerto Rico’s former Secretary of Health and Secretary of the Puerto Rico Healthcare Crisis Coalition:

. . .more than 40 percent of the island’s debt is due to health care and the lack of funding from Medicaid in particular. This chronic underfunding has caused cutbacks in services, a major physician exodus, life-threatening delays in getting appointments and huge delays in payments to hospitals and other medical providers. Patients are suffering and the system is crumbling.

Rationing Due to Inadequate Funding in the Indian Health Service

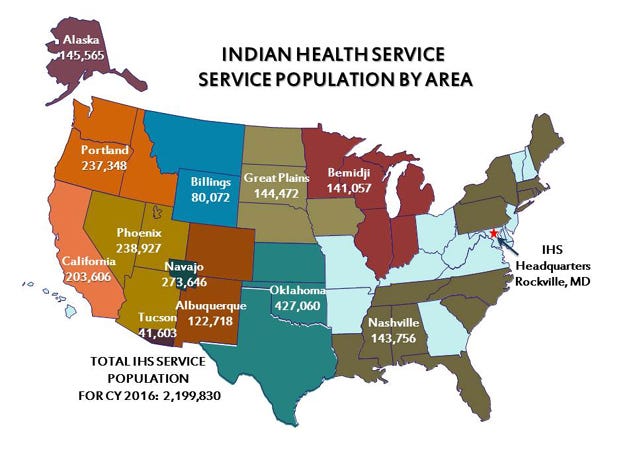

Despite the federal government’s trust responsibility to the Native American people, the federal government provides an annual funding appropriation to the Indian Health Service (IHS) every year. Much like a block grant, the amount provided is not based on need and is rather arbitrary. In fact, according to the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI):

In 2013, the IHS per capita expenditures for patient health services were just $2,849, compared to $7,717 per person for health care spending nationally. Compared to IHS calculations of expected cost for a blend of Federal Employee Health Benefits, average IHS per user spending in 2013 was only 59 percent of calculated full costs. The actual percentage varies between IHS areas, with some funded at much less than 59 percent of need.

Funding shortfalls lead to extreme forms of health care rationing, and the consequences are devastating. Due to severe shortfalls in funding, Native Americans are familiar with the refrain “don’t get sick after June” because that is often when federal funding runs out. At that point, Senator Byron Dorgan (D-ND) explains:

If your illness is not threatening your life or your limb, you are out of luck. That is rationing. That is health care rationing, and it is an outrage in this country. It is happening in a quiet way, inflicting misery all across this country on the first Americans. . . .

During my more than a decade of time working on Capitol Hill, members and staff frequently heard disturbing stories, such as women who were diagnosed with cervical cancer but asked to postpone treatment until the new fiscal year began and children with ear infections who were denied services until is was clear they were suffering from hearing loss.

As for the impact of such rationing, NCAI reports that the American Indian/Alaskan Native (AI/AN) life expectancy is 4.2 years less than the rate for the overall U.S. population. NCAI adds:

According to IHS data from 2005–2007, AI/AN people die at higher rates than other Americans from alcoholism (552 percent higher), diabetes (182 percent higher), unintentional injuries (138 percent higher), homicide (83 percent higher), and suicide (74 percent higher). Additionally, AI/AN people suffer from higher mortality rates from cervical cancer (1.2 times higher); pneumonia/influenza (1.4 times higher); and maternal deaths (1.4 times higher).

Rejecting Block Grants to Protect the Health of Our Nation’s Children

Arbitrary caps and funding levels has led to rationing and terrible health outcomes. Congress knows this and should commit to repealing the Medicaid block grant that is imposed upon and harms Puerto Ricans and address the underfunding of the IHS that harms Native Americans.

Congress should also agree not to turn back the block on the enormous gains that have been made in children’s health coverage across the country because of Medicaid and CHIP. With the uninsured rate for children having fallen to less than 5 percent, now is not the time to backtrack on two decades of success and hard work in advancing children’s health coverage.

If we want to protect our nation’s children from harm, we must demand that Congress reject Medicaid block grants and the related rationing of care and services that such a system would impose upon our nation’s children.

This was originally published on Medium.