Ten-year-old Andrés Jiménez was looking forward to the end of summer. Not because he was particularly eager to return to school, but because the end of summer was meant to be the president’s deadline for taking action on immigration.

But Obama’s deadline came and went, and with it Andrés’s hopes of reuniting his family after his father was wrenched from his life three years ago.

Andrés was seven when his father, after whom he is named, was stopped for driving with an expired licence plate, an event that would unravel the life his parents had worked so hard to build.

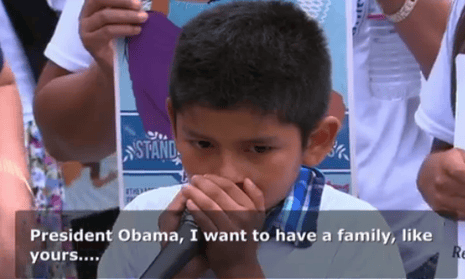

At a rally for immigration reform in Washington DC last month, the young Andrés begged President Barack Obama to take executive action on immigration policy and help reunite families like his own who are torn apart by deportations.

“President Obama, I want to have a family like yours,” Andrés said slowly in Spanish. And then, in a heart-rending moment captured on national television, the young boy breaks down in tears as he talks about his father’s deportation.

Speaking to the Guardian, Andrés said that he cried because he was remembering the day his father was deported.

“They let us hug him and then they took him away,” he said, speaking English. “It makes me sad to think about.”

Obama, facing mounting pressure from his own party, decided last month to postpone taking the decisive executive action he promised on immigration until after the midterm elections in November, infuriating many reform activists and Latinos. But with Congress divided, Obama is the best – if not the only – hope they have for reform on immigration.

While Andrés may be too young to understand the bitter partisan rancour that encases America’s immigration debate, he certainly understands better than most the high price of a broken system – one in which an expired licence plate can lead to deportation.

Life before a deportation: ‘I was happy’

There was a time before Andrés Sr was deported when the Jiménez family lived what many would call the American dream.

He and his wife, Lucía, came to the US desperate and poor nearly two decades ago, in search of a better life than their native Guatemala could provide. They eventually settled in Homestead, Florida. Andrés Sr found a well-paying construction job and the young couple started a family.

This article includes content hosted on player.theplatform.com. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as the provider may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click 'Allow and continue'.

The couple lived in a nice apartment; they owned a car and sent their children to a private Catholic school. At the time, they had four American children – three girls and a boy – with one more on the way. This was the better life they’d hoped for when they left Guatemala.

“I was happy,” the younger Andrés said, remembering what it was like to have his father at home.

One day, Andrés Sr was pulled over for having an expired licence plate. When he couldn’t provide the necessary identification, the immigration officials were called. Andrés Sr spent months in a detention facility in Florida before he was forced to return to Guatemala, where he had nothing, save for his sad history of poverty. Before he was deported, he was allowed to say goodbye to his children and his pregnant wife.

The families left behind

Andrés became the man of the house suddenly at age seven. He doesn’t like to think about that day: “It makes me really sad.”

Financial instability is the most immediate impact of a detention or deportation. In her research, Molly Scott, a senior research associate at the Urban Institute, said she witnessed high rates of food and housing insecurity among families that lost a deportation.

Studies have shown that the threat of deportation causes severe stress and anxiety among children with undocumented parents or siblings. A 2013 report by Human Impact Partners found that nearly 75% of undocumented parents reported that their children had experienced symptoms of PTSD.

In her research, Scott said many of the children reported having a sleeping disorder, such as night terrors or insomnia, or stress-related health problems. She said there are many ways the children display their stress: some develop a strong fear of law enforcement, some act out in school, and others become withdrawn from family and friends.

Andrés said he worries often about his mother. “I’m afraid they’ll take her too,” he said. Without a legal guardian in the US, children are often placed in protective services.

The Obama administration has directed immigration officials to prioritise the deportation of people with criminal records and prior immigration violations over undocumented immigrants who have strong family ties to the US. Even so, deportations continue at record levels – nearly 438,500 expulsions in 2013, an increase of more that 20,000 removals since the previous year.

Lucía is not willing to take this chance. She recently decided to sign over guardianship of her children to Nora Sandigo, a fairy godmother of sorts.

Florida’s fairy godmother

Sandigo is a guardian to more than 800 American children whose immigrant parents have decided not to gamble on the US foster care system. Like Lucía, the parents have all signed paperwork entrusting Sandigo with their children in the event they’re deported.

Aided by her small Miami-based charity, American Fraternity, Sandigo cares for immigrant families broken by deportations like the Jiménezes, whom she provides with food, school supplies and shelter. If, and when, the parents are deported, Sandigo raises their children.

Sandigo’s work is remarkable, but she says she has no choice. “We are tired but we cannot stop doing what we’re doing,” she said. “Every single day the kids need to eat. Every day they need to go to school.”

Sandigo said she does her best to keep the families well-fed and happy given the circumstances, but limited resources and hundreds of children, it’s not always easy. She said a child once told her that he was excited to go to bed early. When she asked him why, he said: “I don’t think about being hungry when I’m sleeping.”

“This kills me,” she said. “But their smiles, they make it all worth it.”

Sandigo brought a group of children including Andrés to Washington DC, last month to rally for immigration reform. She said the experience was positive; the children shared their stories with several lawmakers who seemed sympathetic enough. But after years of pushing for immigration reform, Sandigo knows the difference between a kind smile, a promise and action. She said she is being careful not to get her hopes up, again.

At the rally, Andrés, clutching the microphone near his face with his small hands, addressed the president directly. “I asked him to stop separating families because it hurts me,” he said.

Hope for November

Between the end of summer and the November elections, more than 70,000 immigrants will be deported, according to an estimate by United We Dream that is based on current rates. Immigration groups expect Obama to curb deportations and grant relief to the millions of undocumented immigrants currently living in the US. But even if Obama were to usher in sweeping new reforms, it’s uncertain they would help Andrés get his father back.

Wendy Cervantes, vice-president of immigration and child rights policy at First Focus, a bipartisan advocacy group, said the options for parents who have already been deported are limited at present.

“The only opportunity we have now for parents who have been previously deported is to wait for immigration reform to come up again [in Congress], or for the administration to consider some kind of potential relief as part of whatever announcement they make in the fall,” she said.

Cervantes said the conversation on possible actions the president could take are focused mostly around the undocumented immigrants living in the country. Although, she noted that both omnibus immigration bills included provisions that would have allowed deported parents of US citizens who met certain requirements to apply for citizenship.

Meanwhile, Sandigo said it’s becoming harder for her to tell the children that it will be all right, because she’s not sure it will be.

“It’s hard,” she said. “Sometimes, I cry with them. It’s so hard for them to understand. It’s too much for them to handle.”

Andrés asks me often, ‘When will this problem be fixed?’ I tell him, ‘Nobody except the president can do something.’”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion