Child poverty in this country last year dropped to the lowest rate ever recorded and, according to new research, has declined by nearly 60% over the last three decades. This astounding news dramatically illustrates the power of poverty-fighting initiatives and proves a single, profound truth: Ending child poverty is a policy decision.

One that many lawmakers still haven’t made.

According to the Supplemental Poverty Measure, which includes government assistance such as tax credits, income supports, and nutrition assistance, U.S. policies cut the national child poverty rate nearly in half in 2021, dropping it 4.5 percentage points to 5.2%, the biggest year-to-year decline on record. The research organization Child Trends has tracked a 59% decline in child poverty since 1993. Both analyses identify multiple factors in these declines and highlight the outsized role of public policy improvements through government action.

The proven ability of lawmakers to cut child poverty nearly in half in a single year, especially in the midst of a pandemic, provides evidence that we know how to reduce child poverty and that we have the tools to end it completely — if we choose. The news of these historic declines should not allow lawmakers, advocates, and policymakers to declare victory, but rather pledge to finish the job.

What we know:

Tax credits wield extraordinary power to cut child poverty.

In 2021, Congress temporarily improved the Child Tax Credit by raising the amount of the credit, offering it monthly for half the year, and making children whose families have little or no income eligible for the full credit for the first time. These improvements are largely responsible for reducing child poverty by 46% in 2021, lifting nearly 3 million children — including 1 million children under age 6 — above the poverty line. They also contributed to narrowing the racial poverty gap, reducing poverty levels for Black, Hispanic, Asian and American Indian, and Alaska Native children to the lowest on record.

Families spent their Child Tax Credit on food, child care, clothing, educational materials, and other basic necessities for their children. Some parents and caretakers reported that this additional money gave them a lifeline, others said it gave them a cushion so they weren’t constantly worried about making ends meet. They said it made them feel like lawmakers cared about them, and felt that their struggle was finally being recognized. Increased household income also reduces parental stress, giving parents more time and mental energy for their kids.

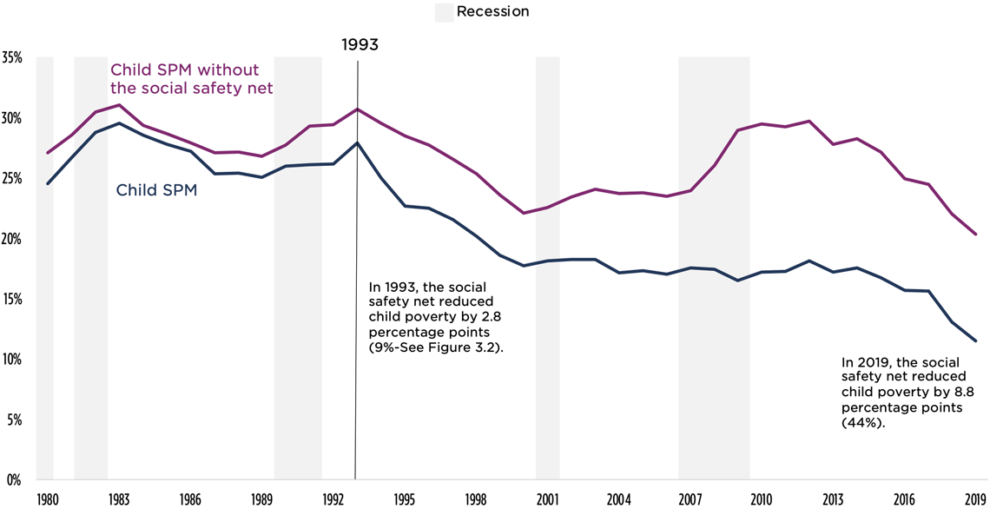

As documented by Child Trends, the role of the social safety net in reducing child poverty grew substantially from 1993 to 2019, with the expansions of the Earned Income Tax Credit responsible for much of the decline in child poverty along with standout economic and labor market factors including overall lower unemployment rates, increases in single mother labor force participation, and increases to state-level minimum wage. However, Child Trends finds that even though the social safety net currently lifts more children out of poverty than in the 1990s, their economic well-being is roughly the same. Because the EITC is directly tied to earnings, it is much less helpful for years when families experience significant stretches of unemployment or very low earnings. Given the volatility and unpredictability of the labor market for low-wage, hourly workers who do not control their schedules and often receive few or no benefits such as paid family leave, sick days, or other supports that make it possible for a parent to maintain work, the EITC must be paired with a fully refundable CTC so that children have consistent access to resources, particularly critical during tough economic times.

Work requirements don’t work:

More than 25 years of the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program and findings from a 2019 nonpartisan, landmark study from the National Academy of Sciences confirm that tying work requirements to benefits does not reduce poverty or boost economic security for families. Instead, these requirements create bureaucratic hoops for parents or caretakers who often already are working, with no flexibility for the volatile nature of the job market, particularly the low-wage job market, and no support for families to overcome the barriers they face to obtaining employment that will provide them with economic stability. Work requirements have drastic consequences for children, undermining access to programs that improve children’s health and educational outcomes.

The past year also demonstrated that expanding the Child Tax Credit significantly reduced material hardship and household food insecurity with “no significant differences in the changes in employment between December 2020 and December 2021 for adults who received the payments and adults who did not receive the payments.” In fact, the Child Tax Credit helps families, especially single mothers, increase their labor force participation by allowing them to afford child care, transportation, and other necessities that help them get to work.

The dramatic spike in unemployment rates in the early part of the pandemic alongside school and child care closures make clear that parents and caretakers experience unexpected changes in their employment circumstances, and children in households with frontline, low-wage workers who lack access to affordable child care, paid sick days or paid family and medical leave suffer the most during economic downturns. One of the lessons we must take away from the COVID crisis and its economic fallout is that instead of attaching burdensome work requirements to benefits, we need a system that provides consistent support to children as they undergo critical stages of brain development, and at the same time helps parents and caretakers obtain and maintain employment that provides a steady household income by providing access to paid family and medical leave, affordable child care, transportation support, job training, affordable higher education and more.

Parenting and Caretaking is work

Our society’s view on the type of work that “deserves” compensation is also deeply flawed. Child rearing and caretaking of family members results in large gains to the collective whole, yet goes uncompensated. Elderly grandparents caring for grandchildren, parents with disabilities, or parents caring for children with disabilities or special health care needs have particular barriers to economic security. We can become a nation that values our families by recognizing these contributions and the way they underpin our country’s economic success.

“Deservedness” standards deliberately create winners and losers

The anti-poverty programs created prior to the pandemic helped significantly reduce child poverty over the last three decades, as Child Trends points out, but the assistance landed largely on children whose caretakers were able to maintain their employment. This program design specifically — and deliberately — excludes children with the greatest needs, creating winners and losers, and perpetuating disparities and injustices that are entwined with our country’s long history of systemic racism and discrimination. In contrast, the improvements Congress made in 2021 — in particular, the expansion of the Child Tax Credit — help get aid to the children who need it most.

Children of color, including Black, Hispanic, American Indian, and Alaska Native children, continue to experience poverty at a higher poverty rate than their white peers. Children in immigrant families face higher poverty rates than their nonimmigrant peers because they often remain ineligible for assistance due to drastic exclusions passed in the 1990s. Children living in Puerto Rico and the other U.S. territories are not accounted for in federal poverty data and they lack equal access to federal benefits as part of a long history of racism and discrimination against Americans living in the territories.

The government’s definition of “poverty” also poses problems. The poverty threshold in 2021 stood at roughly $30,000 for a family of four with two children. The Economic Policy Institute’s Family Budget Calculator shows that in most areas of the country, a family of four with two children needs at least $80,000 a year to have an adequate standard of living — and in many places, they need much more. By these standards, even families who live at double the poverty threshold cannot make ends meet. A realistic view of material hardship and deprivation must figure into calculations of progress to ensure that anti-poverty measures are making a meaningful impact.

Conclusion

While this recent progress on child poverty is unprecedented and worth celebrating, it is not the final word. According to Columbia University’s Center on Poverty and Social Policy, roughly 4 million children slipped back into poverty in January 2022 after Congress allowed the improvements to the Child Tax Credit to expire. The expiration of the CTC improvements and other aid, combined with high food costs and rising rents, sent many families with children back to experiencing significant material hardship. Congress must immediately extend the CTC improvements to avoid further backtracking on this historic progress

American voters agree: By a 72-21% margin, likely voters polled in a recent survey by Lake Research Partners support the 2021 improvements to the Child Tax Credit, with the majority expressing intense support. A large majority of voters —a 6-to-1 margin — also believe the country invests too little in reducing child poverty.

Fortunately, First Focus Campaign for Children’s Congressional Champions continue to insist that improvements to the CTC are included in any end-of-the-year legislative measure that would provide tax breaks for big corporations. In a joint statement, Senate Democrats Brown (OH), Bennet (CO), and Booker (NJ) and Democratic Representatives DeLauro (CT), DelBene (WA), and Torres (NY) urged passage of CTC improvements before the end of the year: “We should have never allowed this critical program to lapse, and we should not extend corporate tax breaks at the end of this year without also extending the expanded Child Tax Credit.”

Maintaining recent progress is just a start. Even one child in poverty is one too many. Congress must also codify a national child poverty reduction target to build the political will needed to reach all children.

We are not only morally obligated to end child poverty, but it also makes smart economic sense for us to do so. The National Academy of Sciences confirms that reducing child poverty not only has direct benefits on individual children’s healthy development but also delivers a significant return on investment for the U.S. economy.

Our baseline cannot be the status quo. It must be what lawmakers, academics, advocates, media, and the American public now know — clearly and definitively — is possible.