The law and the impact it has on the lives of children is critical to those who are:

- abused and neglected,

- victims of a crime,

- caught in a custody battle between parents,

- living in fear because of gun violence,

- concerned about global warming,

- accused of a crime,

- subjected to corporal punishment,

- victims of human trafficking,

- denied access to services by adults that dismiss or fail to address their needs,

- denied self-determination, agency, and inclusion in society by adults that dismiss their voice,

- punished for the actions or status of their parents, or

- discriminated against because of their race, ethnicity, gender (including gender identity and sexual orientation), economic status, disability, religion, immigration status, or age.

At First Focus on Children, we spend enormous amounts of time working on addressing the best interests and unique needs of children in policymaking at the federal, state, and local levels of government. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court and the federal courts are often overlooked by us and other child advocates as to the important role that they play in our society on matters impacting children and youth.

However, that failure is, in part, the product of a judicial system that has historically treated children as the property of their father (colonial times) or parents (20th century).

As Barbara Woodhouse, professor of law at Emory University, writes about our nation’s inception in an article entitled “The Constitutionalization of Children’s Rights”:

. . .the Constitutional text of 1789 lacked the broad statements about equality found in the more revolutionary Declaration of Independence of 1776. This is hardly surprising since the delegates who opposed slavery had been forced to strike a bargain which continues to haunt us [over] two hundred years later.

Woodhouse adds:

The American experience shows how difficult it can be to transcend the limitations of a flawed vision of vested property rights and an incomplete vision of liberty and equality. In 1789, each of the subjugated and excluded categories named — blacks, Indians, women, children, landless laborers, indentured servants — were almost universally perceived as lesser and limited beings. Often, they were not civil persons at all, but rather a form of property or quasi-property, belonging to the patriarch or head of household, and subject to his virtually unchecked authority.

Like other subjugated groups, children have made progress over the last two centuries since our nation’s founding, but gains have been limited. Woodhouse explains in “Who Owns the Child”:

Modern historians generally depict American family law as having undergone a process of transformation, from the hierarchical, patriarchal model of the family of colonial times toward a more egalitarian model. Under the earlier patriarchal model, the father’s power over his household, like that of a God or King, was absolute.

The government now has an accepted role in protecting children and, in some cases, parents and the government are expected to act in the “best interests of children.” Anne C. Dailey and Laura A. Rosenbury explain in “The New Law of the Child”:

Analysis may be best conceptualized as an inverted triangle, with parents and the state occupying the top points and children the bottom. Lines of authority connect the three points, as courts and legislatures specify when parental authority over children trumps state interests, when state interests trump parental authority, and the rare instances when children’s desires trump both.

The system works best for kids when parents and government (executive, legislative, and/or the courts) are: (1) acting in the “best interests” of children; (2) recognizing their duties and responsibilities toward children; and, (3) including and respecting the voice and agency of children in their own lives.

Moreover, there are critical moments when children need to have their rights affirmed and protected from parental authority, governmental authority, or both parents and government, such as when parents have abused their children and government falls to protect children in a poorly performing foster care system.

Unfortunately, it is at these times, when the rights of children most need to be affirmed and supported, that the inverted triangle often fails children. As Woodhouse points out in her book Hidden in Plain Sight: The Tragedy of Child Rights from Ben Franklin to Lionel Tate, the subjugation of children in our legal system is both shocking and sweeping:

Most would be astonished to learn that abused and neglected children in state custody have fewer rights than accused criminals. While a long line of Supreme Court cases has addressed the rights of adults to counsel when taken into state custody, to protection of their property from unjust takings, and to protection of their familial ties, the Supreme Court has never held that a foster child has a right to legal representation, a right to speak in his own court case, a right not to be deprived of property without due process, or a right to contact with his family.

Dailey and Rosenbury add:

One need not master the field of children and law to recognize that our legal system denies children basic personal, social, and political rights.

Senate Judicial Confirmation Hearings Should Include a Focus on Child Rights and Protections

Consequently, during the Supreme Court confirmation hearings for Amy Coney Barrett in the Senate, we heard a great deal about her seven children but little else with respect to children. Senators showered numerous questions and attention upon her children and Barrett often referred to them as well. They are adorable, and I absolutely congratulate and applaud Judge Barrett for her accomplishments as both a teacher and a parent.

However, other matters should disturb advocates for children. For one, there is her service on the board of directors of Trinity School, Inc. in South Bend, Indiana, which had a policy not to accept children of unmarried or single and same-sex parents. Such a policy clearly discriminates against certain children and their parents and violates basic standards of equal protection that children deserve.

This tweet thread from Sam Spital, Director of Litigation at the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, highlights some of the important issues and standards this policy raises for children.

Moreover, when it comes to children, the Senate should have engaged far more on the important issues before the courts on the rights and protections of children. While judges seeking Senate confirmation should definitely talk about their family, they must be asked and be able to explain to the Judiciary Committee their philosophy on how the courts impact (or fail to impact) the rights and protections that other people’s children need and deserve.

As an example, Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ) asked questions about fundamental human rights issues related to family separations and the caging of asylum-seeking children. Unfortunately, Judge Barrett refused to answer those questions or discuss her views on how children in desperate need of help and protection should be treated by our government and the federal judiciary.

What is right for children should not be treated as if it is simply an issue of “policy” or “hot political debate,” as Judge Barrett argued. It is, instead, as Sen. Booker pointed out, “an issue of fundamental human rights, human decency, and human dignity” in which cruelty to children was the purpose in order to “send a message” of “deterrence” to asylum-seekers.

In fact, it is shocking that many conservatives, who often speak about “family values,” are supportive of and complicit in the governmental intrusion into and destruction of families, the denial of basic parental rights, and the short- and long-term harm this policy has upon innocent children. This policy of self-acclaimed “zero tolerance” is nothing less than government imposed and enforced cruelty, kidnapping, and child abuse.

Furthermore, the Trump Administration adopted this policy even though the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) estimated it would have separated 26,000 children from their parents. Although public outcry caused the Trump Administration to say it would end the policy, it has continued but in a more limited way.

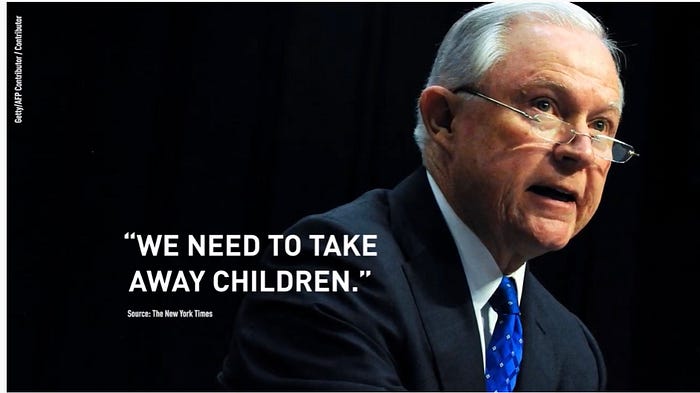

Again, cruelty to children was, in part, the very purpose of this policy. Then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions argued, “We need to take away children.”

And despite strong objections from U.S. attorneys along the border about the policy and its impact on children, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein pushed for family separations to proceed even if the action involved harm to infants.

And once a federal court and public outrage resulted in a halt to widespread family separation, the Trump Administration changed tactics to deterrence by abuse, arguing in court that they should not even have to provide the children and families in border facilities with basic “safe and sanitary” services such as dry clothing, soap, towels, showers, toothbrushes, pillows, or sleep.

Furthermore, despite the fact that a federal judge ruled that separated children and families must be reunited, a new report finds that 545 children remain separated, as many parents were deported by the federal government before being reunited with their kids.

These are fundamental human rights abuses directed at children with tragic and lifelong consequences. As the executive branch went down this catastrophic path, despite clear guidance that “the best interests of the child” should be the governing policy in the treatment of asylum-seeking children, the federal judiciary needed to step in as a check to protect children and families from harm inflicted on them by the government.

Thankfully U.S. District Judge Dolly Gee repeatedly ruled that the government could not violate the basic human rights of children and their families, including numerous rulings against the government’s repeated attempts to gut or ignore the “Flores Settlement,” which dictates that children are treated humanely while in custody and are granted a reasonably prompt release from detention.

U.S. District Judge Dana Sabraw also ruled that the practice of family separation “shocks the conscience.” The Judge added:

These allegations sufficiently describe government conduct that arbitrarily tears at the sacred bond between parent and child. Such conduct, if true, as it is assumed to be on the present motion, is brutal, offensive, and fails to comport with traditional notions of fair play and decency.

Judges Gee and Sabraw are correct.

With respect to Judge Barrett, I can certainly understand that she might not be able to speak to cases that may come before the Supreme Court. However, she could have, at the very least, discussed what the intersection is between parents, governmental authority, children, how she believes children should be treated by the law, and whether children have basic and fundamental rights and protections.

In addition to the issue raised by Sen. Booker regarding family separations and the caging of children, most of the Democratic members of the Senate Judiciary Committee raised important issues related to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Judge Barrett’s previous statements of hostility toward the Act. Some of the members raised some of the issues of particular importance to children if the ACA were to be struck down by the case going before the Supreme Court a week after the 2020 presidential election (First Focus on Children’s amicus brief, which highlights many of the issues of importance to children in this case, is available here.

According to new estimates by the Urban Institute, 1.7 million children would lose coverage if the ACA were overturned by the Supreme Court, which would increase the uninsured rate for kids by 48 percent.

In addition, Sen. Mazie Hirono (D-HI) was unable to get much in the way of answers from Judge Barrett about her dissent in a case seeking to overturn the Trump Administration’s administrative changes to what is known as “public charge.” As a point of fact, the Trump Administration’s proposed rule “automatically considers being under the age of 18 as a negatively weighted factor, thus punishing children simply for their age.” That was not acknowledged in Barrett’s lengthy dissent defending the Trump Administration’s policy.

Unsurprisingly, the impacts of the Administration’s policies are already having measurable negative consequences on the enrollment of children in Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP or food stamps), and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), including U.S. citizen children of immigrants. In an article published in Health Affairs, researchers at Ideas42 estimate that 260,000 children lost health coverage as a result of the proposed public charge rule.

In a number of ways, the regulatory assault and legal challenges to the health and well-being of kids are significant. It seems that if Judge Barrett really cares about children that she could have at least engaged in a discussion as to what the role of the courts should be in protecting children from harm.

Originalism Poses a Threat to the Consideration of the Rights of Children

Without a discussion as to Judge Barrett’s overall philosophy regarding the rights and protections of children, we are left only with her declaration that she is an “originalist.” Describing the judicial philosophy of originalism, Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the law school at the University of California, Berkley, explains:

Originalists believe that the meaning of a constitutional provision is fixed when it was adopted and that it can change only by constitutional amendment. Under this view, the First Amendment means the same thing as when it was adopted in 1791 and the 14th Amendment means the same thing as when it was ratified in 1868.

But rights in the 21st century should not be determined by the understandings and views of centuries ago. This would lead to terrible results. The same Congress that voted to ratify the 14th Amendment, which assures equal protection of the laws, also voted to segregate the District of Columbia public schools. Following originalism would mean that Brown v. Board of Education was wrongly decided in declaring laws requiring segregation of schools unconstitutional.

Judge Barrett and other “originalists” have a difficult time reconciling their judicial philosophy with certain landmark court decisions, such as Brown v. Board of Education (1954). In Barrett’s “Originalism and Stare Decisis,” she even quotes Michael Gerhardt saying, “Originalists . . . have difficulty in developing a coherent, consistently applied theory of adjudication that allows them to adhere to originalism without producing instability, chaos, and havoc in constitutional law.”

While some originalists argue that legal precedent or stare decisis would likely prevent the overturn of landmark cases, it fails to negate the likelihood that, as Dean Chemerinsky points out, school desegregation, changing monetary policy from the gold standard, and the passage of New Deal programs like Social Security would likely have been ruled unconstitutional if left up to originalist judges.

This should be disturbing to child advocates and highlights why this approach poses significant present and future challenges for children.

The problem is that originalists like to refer back to the Founders for guidance on the original meaning of the Constitution. Unfortunately, at our nation’s inception, children were absent from the document, and children were legally treated as the property of their father. Kids had no or limited rights. As Barbara Woodhouse points out in Hidden in Plain Sight:

When they declared it self-evident that all men were created equal, they certainly did not mean to emancipate their slaves, their women, or their children.

It has taken decades to slowly transform the way children are treated by the law. Woodhouse explains:

As late as 1920, a parent who killed a child in the course of punishment could claim a legal excuse for homicide in no fewer than nine states. Well into the nineteenth century, a father could enroll his male children in the army and collect the enrollment bounty, betroth his minor female children to persons of his choice, and put his children to work as day laborers on farms or factories and collect their wage packets.

But family law did evolve. According to Woodhouse:

As family law matured, American law increasingly characterized parents as the guardians not the owners of their children. Parental rights were regrounded in the presumption that parents are motivated by love for their children, share a deep commitment to their children’s future, and will act in their children’s best interests.

Parental rights were not diminished, but as the law began to recognize that people other than white men with property had rights too, children were recognized as also having modified rights. Woodhouse writes:

Although children are never mentioned in the U.S. Constitution, courts have held that various rights apply to children as well as adults. Usually, the rights are modified to meet the special situation of children. Examples of constitutional rights that apply to children as well as adults are the right to a fair trial, the right to be free from race and gender discrimination, and the right to religious and intellectual freedom.

But if left to originalists, even that limited progress would have been virtually impossible. Justice Clarence Thomas is an originalist and his written opinions highlight how this philosophy threatens any future progress for children and may instead lead to significant backsliding and harm.

Josh Blackman, professor of law at the South Texas College of Law, refers to Justice Thomas’s judicial philosophy as “parental paternalism.” Blackman describes:

First, this broad view of parental paternalism continues a philosophy that Thomas discussed in his opinions in Troxel v. Granville, Morse v. Frederick, Safford v. Redding, and most recently in Turner v. Rogers. Broadly stated, he does not view minors as holders of rights, and puts a lot of stake in parents (specifically a “nuclear family”) to protect the interests of the child. When there is any doubt, Thomas will side with the parents. . . .

Judge Thomas would cut children out of the inverted triangle. He believes that children have limited or no rights, based on his interpretation of what he thinks the Founders believed. In his concurrent opinion for the majority in Morse v. Frederick (2007), he writes:

In my view, the history of public education suggests that the First Amendment, as originally understood, does not protect student speech in public schools.

Thomas goes so far as to argue for overturning the judicial precedent in Tinker v. Des Moines Community Independent School District (1969) that asserted children do have First Amendment rights. According to Thomas:

…early public schools were not places for freewheeling debates or exploration of competing ideas. Rather, teachers instilled “a core of common values” in students and taught them self-control. . . Teachers instilled these values not only by presenting ideas but also through strict discipline. Schools punished students for behavior the school considered disrespectful or wrong. Rules of etiquette were enforced, and courteous behavior was demanded. To meet their educational objectives, schools required absolute obedience.

Justice Thomas implies that schools can also discipline students to the extent they wish short of “excessive physical punishment.”

In Brown v. Merchant Entertainers Association (2011), Justice Thomas takes his judicial philosophy to another level. He writes:

The practices and beliefs of the founding generation establish that “the freedom of speech,” as originally understood, does not include a right to speak to minors (or a right of minors to access speech) without going through the minors’ parents or guardians.

Justice Thomas may have been on the Supreme Court too long since he seems to be unable to fathom a world with the Internet, smartphones, texting, and social media. Instead, Justice Thomas envisions a world in which children have no rights and no agency unless parents or guardians approve.

In Vox, Ian Millhiser points out that Justice Thomas has a history of limiting the scope of First Amendment free speech protections, except when it comes to wealthy donors making campaign contributions. Millhiser writes:

In Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010), the Supreme Court held that the right to free speech includes the right of corporations to spend unlimited money on influencing elections. In a partial dissenting opinion, Thomas complained that Citizens United “does not go far enough.”

Justice Thomas, in other words, envisions a much weaker First Amendment for children, journalists, and, indeed, for muchof the country. But when wealthy donors seek relief from campaign finance restrictions, Thomas takes a maximalist view of their First Amendment rights.

How very convenient.

Originalism is clearly a deep threat to the rights of children in our country. In fact, if you are at all concerned about the rights of children, a potential judge’s adherence to originalist doctrine might be reason for disqualifying that person from the federal bench.

As Dean Chemerinsky writes:

The rejection of originalism is not new. Early in the 19th century, Chief Justice John Marshall wrote that “we must never forget that it is a Constitution we are expounding,” a Constitution “meant to be adapted and endure for ages to come.”

Chemerinsky adds:

It is a myth to say that an “original public understanding” can be identified for most constitutional provisions because so many people were involved in drafting and ratifying them. In teaching constitutional law, I point to the many instances where James Madison and Alexander Hamilton disagreed about such fundamental questions as whether the president possesses any inherent powers.

Moreover, it is a myth to think that even identifying an originalist understanding can solve most modern constitutional issues. Can original public meaning really provide useful insights about the meaning of the Fourth Amendment and whether the police can take DNA from a suspect to see if it matches evidence in unsolved crimes or obtain stored cellular phone location information without a warrant?

This is very true for children. Our society is profoundly different than it was back in 1789 and standards have changed for the better.

But Dean Chemerinsky is also right to point out that there really is no “original public understanding” in most constitutional provisions. There is no doubt that the Founders, just like parents today, have very different beliefs as to how children should be raised.

We Need a New Social and Legal Compact that Recognizes the Rights of Children

Benjamin Franklin was one of our nation’s Founding Fathers, but he undoubtedly had a profoundly different view about the voice and agency of children than Justice Clarence Thomas would ascribe to “the Founders.”

When he was 12, Franklin became an apprentice and indentured to a printer. However, when he turned 17 in 1723, Franklin had been a “political dissident” writing columns under a pseudonym that, as Woodhouse writes:

. . .strongly endorsed the ideas of free speech and free thought, quoting from great thinkers on the nature of freedom. . . At age sixteen, Ben questioned not only colonial but also domestic authority. He relished speaking truth to power, especially when his speech could be clothed in irreverent parody.

Franklin built his own library as a child that was not reliant upon his parents or master (as Justice Thomas pronounced should be the case in Brown v. Merchant Entertainers Association). Woodhouse adds:

Ben’s life illustrates the role played by American youth, even while under the legal control of parents and masters, in defending the right to free speech and the right to speak out against oppression. With the courage of innocence, young people saw what needed changing and believed in the possibility of change. . . To believe that the right to freedom of speech and expression should apply to adults alone would ignore children’s central role in the battle to secure these freedoms.

On his treatment as a child by his master, Woodhouse quotes Franklin saying:

I fancy his harsh and tyrannical treatment of me might be a means of impressing me with that aversion to arbitrary power that has stuck to me through my whole life.

It is that type of tyranny that Justice Abe Fortas cited in his majority opinion in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School District (1969). He wrote:

In our system, state-operated schools may not be enclaves of totalitarianism. School officials do not possess absolute authority over their students. Students in school as well as out of school are “persons” under our Constitution. They are possessed of fundamental rights which the State must respect, just as they themselves must respect their obligations to the State. . . In the absence of a specific showing of constitutionally valid reasons to regulate their speech, students are entitled to freedom of expression of their views.

Justice Fortas adds:

It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.

A few years later, Justice Harry Blackmun writes in Planned Parenthood of Central Missouri v. Danforth (1976):

Constitutional rights do not mature and come into being magically only when one attains the state-defined age of majority. Minors, as well as adults, are protected by the Constitution and possess constitutional rights.

Justice John Paul Stevens, in Troxel v. Granville (2000) also articulated the independent constitutional rights of children in his dissent in the case involving the visitation rights of grandparents. While he agrees with the “presumption that parental decisions generally serve the best interests of their children” but noted that “even a fit parent is capable of treating a child like a mere possession.” Stevens adds:

Cases like this do not present a bipolar struggle between the parents and the State over who has final authority to determine what is in a child’s best interests. There is at minimum a third individual, whose interests are implicated in every case to which the statute applies — the child. . . [T]o the extent parents and families have fundamental liberty interests in preserving such intimate relationships, so, too, do children have these interests, and so, too, must their interests be balanced in the equation.

Our children desperately need a legal system that rejects judicial philosophies that treat children as “chattel” or the property of parents, and assumes that children lack independent reason, agency, or understanding of their own “best interests.” The law should balance the interests of parents (who have a developed relationship with a child), the state’s parens patriae role that should be focused on the protection and “best interests” of the child, and the child’s own expressed interests and needs.

In fact, parents, the state, and children should all strive for improvements in the lives of children, as they are all of our future. Founder John Adams wrote:

It should be your care, therefore, and mine, to elevate the minds of our children and exalt their courage; to accelerate and animate their industry and activity; to excite in them an habitual contempt of meanness, abhorrence of injustice and inhumanity, and an ambition to excel in every capacity, faculty, and virtue. If we suffer their minds to grovel and creep in infancy, they will grovel all their lives.

Unfortunately, there is a political movement that is pushing in the opposite direction. It would eliminate any recognition of the rights of children and gut any affirmative responsibility of the government to look out for the “best interests” of children. Instead, it would enshrine “parental rights” as a “liberty” and “fundamental right” in the Constitution (H.J. Res. 36 by Rep. Jim Banks (R-IN in the 116th Congress but was previously introduced by Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) in the 115th Congress). The proposed “parental rights” constitutional amendment is sweeping and affirms the right of parents to control all aspects of their children’s lives (or as Sec. 1 reads, “liberty of parents to direct the upbringing, education, and care of their children”).

The language would preclude any action by the government, such as laws that address child health, education, child labor, or even the protection of children from abuse “without demonstrating that its governmental interest as applied to the person is of the highest order.” This far more limited standard is focused entirely on “governmental interests,” which is quite different than the historical parens patrie state role that serves to protect the “best interests” of the child in a number of matters, including child protection, child custody, child health, etc.

Although parental rights advocates argue it would “not include a right to commit abuse and neglect,” the proposed constitutional amendment only limits “parental rights” by saying it “shall not be construed to apply to a parental action or decision that would end life (emphasis added).”

There are many “actions or decisions,” such as allowing parents to treat their children as property, denying or withholding basic care or services, requiring forced child labor, and imposing punishment or discipline that would otherwise be considered to be assault and battery and even torture without a result that “would end life.”

Samantha Godwin, a resident fellow at Yale Law School, writes:

When evaluating the extent of parents’ legal rights, we should not merely consider how ideal parents exercise their power to provide the effective care and guidance children need. The extent of what the law enables imperfect parents to do to their children must also be taken into account. The issue is not only what role we hope that parents play in their children’s lives, but how the powers actually granted might be used and abused for better or worse. Thinking only in terms of how the best parents conduct themselves is a mistake; it is also necessary to account for what the worst parents can get away with.

In addition, with a “parental rights” constitutional amendment, parents would be able to demand the government and the courts enforce their “rights” against children who refuse to pay respect, deference, or obey parental directions. The courts could also penalize others that aid or abet “uncooperative” kids. In fact, there are already some laws that can trigger state coercion against children that results in detention, probation, or the forced admission of children to mental health or juvenile detention facilities. Rather than protecting kids, the government’s role would undoubtedly increase punitive actions against children.

Over 30 years ago, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) proclaimed that every child “should grow up in a family environment, in an atmosphere of happiness, love, and understanding” and be raised “in the spirit of peace, dignity, tolerance, freedom, equality, and solidarity.” Unfortunately, the United States is the only nation in the world that has failed to ratify the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

In the 114th Congress, Reps. Luis Gutierrez (D-IL), Karen Bass (D-CA), and Judy Chu (D-CA) introduced H.Res. 476 to encourage the establishment of a national Children’s Bill of Rights that said children have “the unalienable right to live in a just, safe, and supportive society.”

As Georgia State law professor Jonathan Todres writes:

Highly charged rhetoric masks the reality of the CRC and children’s rights more broadly — that is, the fulfillment of children’s rights is consistent with what the vast majority of parents want for their kids. They want their children to have access to health care and education, to be free to observe their faith without government interference, to live without discrimination, and to grow up without suffering violence or exploitation.

Despite the major role the U.S. government played in drafting the CRC and the numerous similarities between U.S. law and the treaty, the U.S. government isn’t likely to ratify the CRC anytime soon.

But given the shared values in what parents dream of and what the CRC mandates for children, the idea of children’s rights remains relevant in the United States. We don’t have to wait passively for government to act; we can take action, guided by children’s rights values.

Todres is right.

It is well past time for child advocates to fully recognize the critically important role that the courts play in the lives of children and to develop a comprehensive judicial advocacy agenda that affirmatively respects and affirms the rights of children. Such an agenda should affirmatively pursue legislative protections in the short-term and a judicial agenda to improve the status and rights of children in the long-term.

The vast majority of parents would agree, and children deserve nothing less.