When it comes to making public policy related to children, the vast majority of Americans support the notion that public policy and government should act in the “best interest of the child” or, at the very least, “do no harm” to children.

Unfortunately, far too often, children are either an afterthought or worse. In the case of Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee’s proposal to convert Medicaid into a block grant or per capita capped program, it is disturbing — but sadly not surprising — that children are actually targeted and disproportionately placed in harm’s way.

A Medicaid block grant or per capita cap is simply an arbitrary financial limit that a state would receive from the federal government to provide health care. According to a recent analysis of the potential impact of recent proposals to cap Medicaid, Avalere Health estimates for a potential loss of federal funding to states, specifically for children, of $93 to $163 billion for FY 2020–2029 nationally. As Avalere explains:

A reduction in federal Medicaid funding would require states to reduce spending in Medicaid or in other areas of their budget. In particular, states may reduce eligibility for coverage, limit access to covered benefits or services, increase beneficiary cost sharing or decrease payment for care. . .

The Tennessee concept paper to radically, and likely illegally, (more on that later) transform the Medicaid program by Gov. Lee’s administration would likely seek a waiver from the Medicaid law from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) later this fall after three public hearings between October 1–3 in Nashville, Knoxville and Jackson, respectively.

Arbitrarily capping the Medicaid program, whether block grants or per capita caps, has been shown to create enormous shortfalls in funding to provide health coverage to low-income senior citizens, people with disabilities, children and adults that receive health coverage. In a review of legislative proposals to impose Medicaid per capita caps in Congress and to address likely significant shortfalls in funding, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) wrote:

. . .enrollees could face more significant effects if a state reduced providers’ payment rates or payments to managed care plans, cut covered services, or curtailed eligibility — either in keeping with current law or to a greater extent, if given the flexibility. If states reduced payment rates, fewer providers might be willing to accept Medicaid patients, especially given that, in many cases, Medicaid’s rates are already significantly below those of Medicare or private insurance for some of the same services. If states reduced payments to Medicaid managed care plans, some plans might shrink their provider networks, curtail quality assurance, or drop out of the program altogether. If states reduced covered services, some enrollees might decide either to pay out of pocket or to forgo those services entirely. And if states narrowed their categories of eligibility (including the optional expansion under the ACA), some of those enrollees would lose access to Medicaid coverage. . . .

This proposal comes at a time when the nation’s uninsured rate is heading in the wrong direction. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the uninsured rate across the country increased from 25.6 million to 27.5 million between 2017 to 2018 or from 7.9 to 8.5 percent.

For children, the Census Bureau finds that the uninsured rate rose from 5.0 to 5.5 percent from 2017 to 2018, which represents an 11 percent increase, and that the overall number of uninsured children rose by 425,000 to 4.3 million.

We should not be heading backward. Every person in this country should have access to high-quality health insurance coverage. Instead of setting arbitrary caps and putting in place the bureaucracy to enforce cuts and limits to care, we should be looking for ways to increase the number of insured Americans, including children, and improving access to health care.

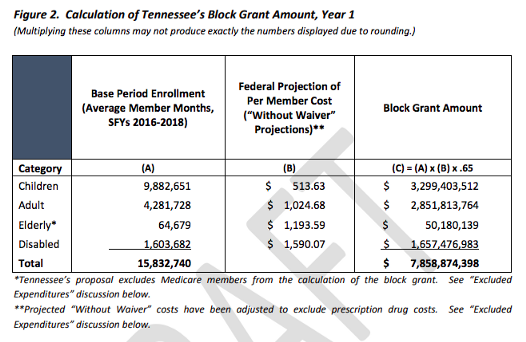

Even worse, Tennessee is proposing to disproportionately threaten the health of children. As Figure 2 in the concept paper shows, children would represent a vast majority of those placed in harm’s way by Gov. Lee’s unique hybrid of a Medicaid block grant and per capita cap (i.e., the 62 percent of children in this chart and another percentage share of people with disabilities subjected to the caps).

Arbitrary Medicaid caps or limits are particularly threatening for children with special health care needs, including infants, kids with cancer, asthma, heart conditions, and children in foster care, because the cost of their care and coverage would, by definition, exceed the average per capita limit included in the proposal for the federal share.

To meet the arbitrary caps, Tennessee and its Medicaid managed care plans would have an incentive to impose bureaucratic barriers to care, paperwork denials, limits and other forms of rationing for Tennessee’s vulnerable and fragile children.

This is particularly disturbing because Tennessee has already demonstrated a desire and ability to use such mechanisms to limit care and services to children. Just a few months ago, a study by the Tennessean found that the state had used a number of mechanisms to limit and ration coverage for its children over the past few years. The investigative report explains:

At least 220,000 Tennessee children were cut, or were slated to be cut, from state health insurance in recent years in an unwieldy TennCare system that was dependent on hard-copy forms and postal mail. . . The majority of these kids likely lost their coverage because of late, incomplete or unreturned eligibility forms.

In an analysis titled The Return of Churn: State Paperwork Barriers Caused More than 1.5 Million People to Lose Their Medicaid Coverage in 2018, Families USA’sEliot Fishman and Emmet Ruff found:

In 2016, [Tennessee] began making manual eligibility redeterminations after still not having an online system to do so. Because redeterminations could not be processed online, the state mailed a 98-page renewal packet to beneficiaries to renew their eligibility. The Tennessee Justice Center, an advocacy organization that has helped Tennesseans and their families to renew their TennCare eligibility, reports that in many cases the state mailed renewal packets to the wrong addresses, and as a result, beneficiaries lost coverage for failing to return renewal packets that they never received. In other cases, the state never processed beneficiaries’ renewal packets despite receiving them (as documented by beneficiaries’ proof of receipt).

Also contrary to federal law, the state failed to screen children for eligibility under other Medicaid categories before disenrolling them, resulting in children losing coverage despite qualifying under another category. Additionally, because the state did not apply the same eligibility information to all members of the same family, parents and caregivers were required to submit separate packets for each of their children, and the state made separate eligibility determinations for each member of a family.

None of this is about striving to improve the health of children and families. At a budget hearing earlier this year, Tennessee State Sen. Jeff Yarbro pushed agency officials about how Tennessee had the highest decline in covered children across the country in 2018. Sen. Yarbro said:

This is utterly broken to the point of where it appears to be more by design than accident. You have to conclude that this is a management decision to trim the rolls or at least let them shrink by relying on people either not receiving, or not completing, the gargantuan applications.

Tennessee was rationing care to children through bureaucratic red tape.

Tennessee’s Proposed Arbitrary Medicaid Cap Targets Kids

Although Tennessee has finally revamped its eligibility process this year, it is disturbing that the state is creating new barriers to the health of children by proposing the vast majority of those that would be subjected to the newly proposed Medicaid caps would be kids [MK1] (Figure 2 above).

Under current law, the federal government and states have a shared partnership (65.21 percent federal and 34.79 percent state)to cover any increase in Medicaid’s costs due to either enrollment or inflation.

This would no longer be the case if Tennessee’s proposed Medicaid cap were approved. According to the proposal:

. . .the financing of Tennessee’s Medicaid program will no longer operate under the traditional Medicaid financing model. Instead of drawing down federal dollars based on a fixed percentage, the federal government will provide a block grant of federal funds to the state for the operation of its Medicaid program.

In short, federal funding would no longer be guaranteed to cover its full share of costs under the program.

Recognizing the potential for significant harm, the Governor specifically exempts most senior citizens (“expenditures on behalf of individuals who are enrolled in Medicare”), outpatient prescription drugs, and Tennessee’s own administrative expenses from the caps in his proposal. In other words, the health of children would be put at grave risk but not administrative costs and bureaucracy.

Consequently, under the draft proposal, federal funding would be allocated to the state in the first year in the form of a block grant and future federal contributions would be limited in the form of per capita payments above a base block grant amount.

According to the concept paper:

Once calculated, the block grant amount will be trended forward from 2018 to the first year of the demonstration using an inflation factor based on CBO projections for growth in Medicaid spending.

First, CBO is often way off in its projections and inflation rates often vary wildly from year-to-year, depending on a number of factors. For example, in the case of natural disasters or some public health crises, Tennessee’s Medicaid would find itself shortchanged at the very moment when it is in need of additional federal support.

Much like the Tennessee proposal, U.S. Sens. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina and Bill Cassidy of Louisiana proposed a Medicaid cap that was supported by President Donald Trump in his FY 2020 budget submission to do much the same but at an inflation rate that would be below the expected medical inflation rate. According to an analysis by Avalere Health, the Graham-Cassidy language would have cut Medicaid payments to children by an astounding 31 percent over a 10-year period.

Tennessee Proposes to End Its Future Commitment to Its Citizens

Even worse than the federal caps, Gov. Lee’s radical proposal also would end Tennessee’s commitment to its share of health costs of citizens covered by Medicaid to what it spends in fiscal year (FY) 2019. According to the concept paper:

. . .the state commits to maintenance of effort with regard to the non-federal share of TennCare funding based on state expenditures on TennCare during state Fiscal Year 2019, trended forward each year the block grant is in effect.

Limiting the state Medicaid contribution to just what was spent in FY 2019 would create significant shortfalls over time. This is particularly true in cases where enrollment and costs increase due to demographic changes, economic downturns, natural disasters, a public health crisis, the discovery of a medical breakthrough or cure, or medical inflation.

The state’s proposal to no longer pay its share of the costs of its citizens in the future is the most disturbing aspect of the proposed Medicaid waiver. Although it is bad enough that the federal government’s commitment or share to the health care costs of those in Medicaid would be arbitrary capped, even worse, Tennessee would no longer cover a dime of any additional future expenses.

This quickly becomes a significant problem since Tennessee currently pays for more than one-third (34.79 percent in FY 2020) of the costs of Medicaid coverage. Under Gov. Lee’s proposal, it is difficult to see how Medicaid would cover newly enrolled infants, foster children, children with cancer, people with disabilities, or people who would need Medicaid coverage in the wake of an economic downturn or natural disaster.

To address the subsequent shortfall, Tennessee assumes federal officials would be willing to give the state “flexibility” to use their “block grant” to:

- Withhold certain medical benefits, such as mental health, dental coverage, or new treatments (Tennessee is asking to waive amount, scope, and duration benefit requirements and to limit access to Food and Drug Administration approved prescription drugs under current Medicaid law);

- Slash payment rates to hospitals, clinics, doctors, dentists, and pharmacies; and,

- Cut children, pregnant women, people with disabilities, or low-income senior citizens off of coverage.

Despite the strange allure to some state officials of the word “flexibility,” block grants and per capita caps do not come with some sort of magic wand. “Flexibility” does not make children, senior citizens and people with disabilities mysteriously less expensive to cover without significant cuts to benefits, services or provider payment rates.

This is one of many reasons Medicaid block grants are such terrible public policy.

Tennessee’s Proposal is Likely Not Legal

Tennessee’s proposal to cap both the federal and state payments in Medicaid would likely be found to be illegal if challenged in the courts. According to a Health Affairs analysis by Rachel Sachs and Nicole Huberfeld entitled “The Problematic Law and Policy of Medicaid Block Grants,” Medicaid law allows Section 1115 demonstration waivers “to allow states to experiment with certain aspects of the Medicaid program to improve beneficiary coverage or care.”

However, Tennessee’s waiver proposal does nothing to improve beneficiary coverage or care and it does nothing to further the intent and objectives of Medicaid law.

Moreover, as Sachs and Huberfeld explain:

Medicaid spells out federal payment within Section 1903, which states that the HHS secretary “shall pay to each State…the [federal match] of the total amount expended…as medical assistance under the State plan….” This language is not waivable under Section 1115, which explicitly permits waivers of Section 1902 but not Section 1903. (HHS can approve more spending than Section 1903 contemplates to match a state’s expansion of Medicaid coverage, but it cannot waive Section 1903.) As a result, HHS cannot cap the Medicaid funds it disburses to states, either per person or programmatically, because it must pay the federal match for the “total amount” of a state’s spending.

Nicholas Bagley confirms this point in a blog titled “Tennessee wants to block grant Medicaid. Is that legal?” for The Incidental Economist. He writes:

You can’t use section 1115 to waive section 1903. To the contrary, section 1903 is pointedly omitted from the list of statutory provisions that HHS is empowered to waive.

So you can’t use Medicaid waivers to change Medicaid’s financing structure. And that’s exactly what Tennessee is proposing to do.

Conclusion

Tennessee was once considered a national leader in health care policy. In 1994, Tennessee launched TennCare by using savings from the use of Medicaid managed care to expand health care coverage to the uninsured. Mandy Pelligrin of the nonpartisan Sycamore Institute explains, “This was considered the most expansive Medicaid eligibility in the country at the time.”

Unfortunately, rather than seeking innovative ways to expand and improve health coverage of its citizens, now Gov. Bill Lee and the Tennessee legislature are moving in the opposite direction and proposing an arbitrary cap on both the federal and state shares of Medicaid. This would lead to limits and the rationing of health care services for low-income children, some senior citizens, people with disabilities and adults.

Our elected officials should protect children rather than putting them in harm’s way. When it comes to policies that impact children, the “best interest of the child” should be the standard.

Unfortunately, placing arbitrary fiscal limits on the health of kids does nothing to improve their care. In fact, it threatens their health and well-being, and for that reason, should be soundly rejected.

Children deserve much better.