Our Children are in Crisis

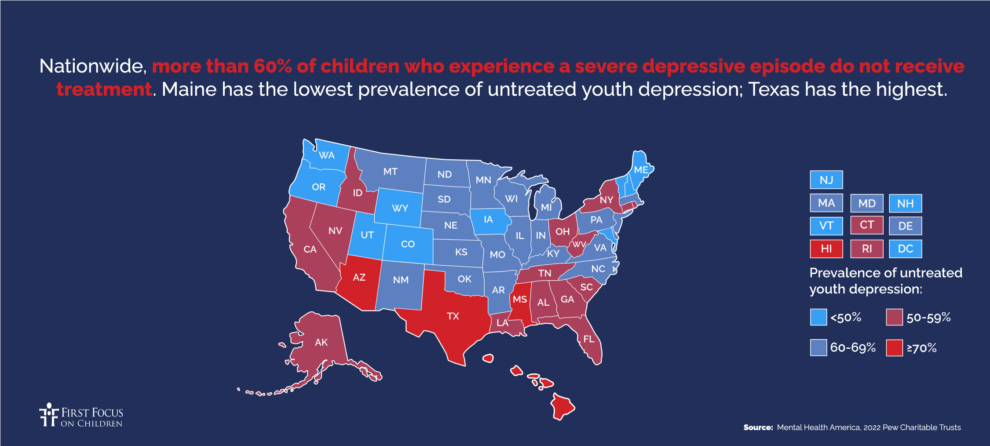

The United States has a severe shortage of pediatric mental health professionals. In fact, typically, 11 years pass between when symptoms first appear and when treatment begins. A heat map produced by Mental Health America in 2022 shows that more than 60% of children who experience a severe depressive episode do not receive treatment. A December 2023 report by the Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA) predicts substantial shortages of child and adolescent psychiatrists, school counselors, and child, family, and school social workers in 2036. In 2022, only two states (Vermont and New Hampshire) were meeting the recommended ratio of school counselors to students.

Public Support for Congressional Action

American voters believe — by a roughly 6-to-1 margin — that the federal government is spending too little on the health, safety, and well-being of our children, according to a poll conducted by Lake Research Partners in May 2022. Support for children’s programs crosses race, gender, and party lines. Voters also believe — again by a 6-to-1 margin — that we are spending too little rather than too much on youth mental health services.

A recent survey by the National Alliance of Mental Illness found widespread public support for Congress to do more regarding mental health.

Increase the Pipeline of Mental Health Professionals to Treat Children and Youth

The U.S. right now spends far too little on mental health in general, and pediatric mental health faces particular obstacles.

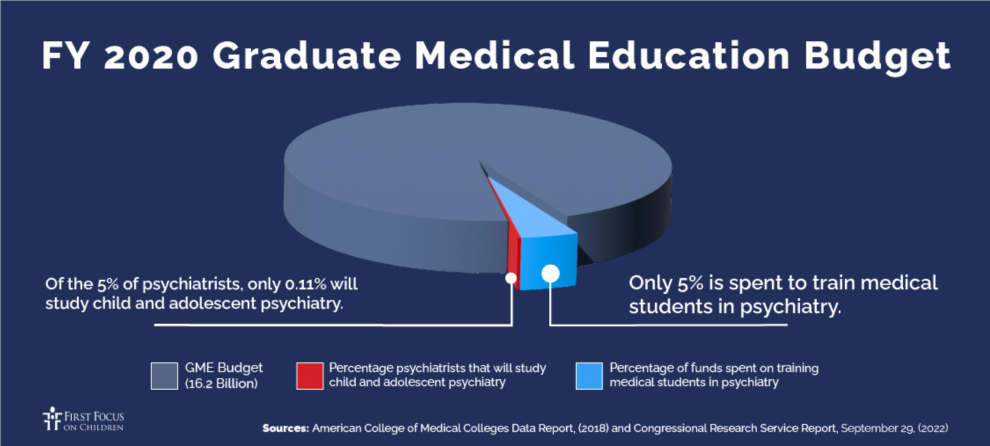

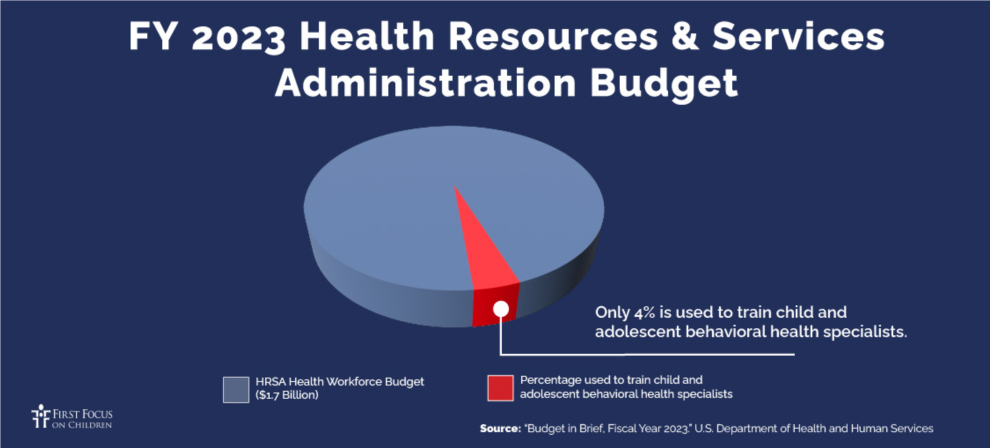

The Graduate Medical Education (GME) program receives roughly $16.2 billion a year in federal funding and provides the primary source of training for the nation’s health care and behavioral health workforce. Of all the students in the GME pipeline, fewer than 5% of students are pursuing psychiatry: Of those students, well under 1% – just 0.11% are pursuing child and adolescent psychiatry. The Health Resources and Service Administration also trains health care professionals. Less than 10% of HRSA’s $1.7 billion workforce development budget is used to develop the behavioral health workforce. Of that budget, just 4% is allocated to training for child and adolescent behavioral health.

As demonstrated by the GME and HRSA budgets, the U.S. woefully under-invests in developing the pediatric mental health workforce. Less than 1% of all GME dollars go toward training child and adolescent psychiatrists. That number alone should sound alarms in Congress. Similarly, only 4% of HRSA’s workforce development budget is spent to train child and adolescent behavioral health professionals. HRSA, which also is tasked with projecting the number of behavioral health professionals the country will need by 2036, expects that demand will continue to far exceed current capacity. Below are some recommendations for bold but necessary actions that Congress can take to ensure that children and youth have access to mental health care:

Recommendations

- Create a Mental Health Service Corps as part of HRSA to increase the number and variety of mental health professionals to serve children and youth

- Appropriate adequate dollars for pediatric mental health workforce development commensurate with the severity of the national need

- Develop a national strategy to assess shortages in the pediatric mental health workforce and recommend ways to grow the mental health workforce over 10 years

- Increase the number of GME slots for child and adolescent psychiatrists

- Include a wider range of mental health professional categories, such as social workers, school counselors, and others, who can receive HRSA workforce program funding

- Place a greater emphasis on HRSA scholarships rather than loan repayment to encourage a wider range of young people from diverse economic backgrounds to enter this profession both for undergraduate and graduate school degrees

- Include youth peer support services like Oregon’s YouthLine as a permanent part of the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline

- Enforce the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) legislation from 2008 to improve access to pediatric mental health providers, and to ensure families have access to providers who accept Medicaid and private insurance.

Written by Elaine Dalpiaz and Averi Pakulis