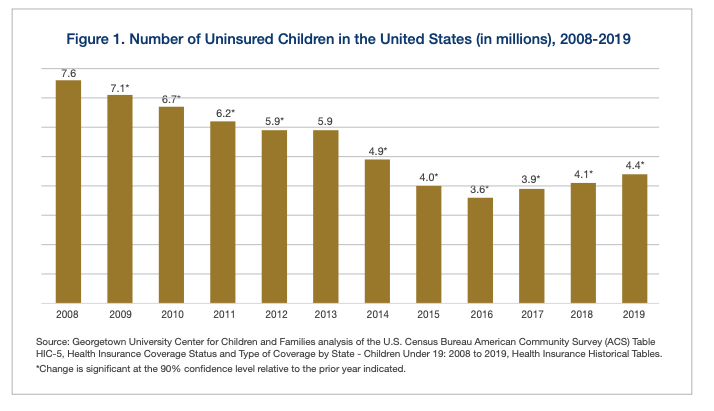

A report released last week by the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families shows the continuation of the downward trend in health care coverage for children that began in 2017. Titled “Children’s Uninsured Rate Rises by Largest Annual Jump in More Than a Decade,” the report finds that since the Trump administration took office, children’s coverage numbers have steadily decreased. The report begins with this:

“After reaching a historic low of 4.7 percent in 2016, the child uninsured rate began to increase in 2017, and as of 2019 jumped back up to 5.7 percent. This increase of a full percentage point translates to approximately 726,000 more children without health insurance since the beginning of the Trump Administration when the number of uninsured children began to rise. Much of the gain in coverage that children made as a consequence of the Affordable Care Act’s major coverage expansions implemented in 2014 has now been eliminated.”

Since the passage of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) in 1997, CHIP and Medicaid have worked together to cover children with child-specific care that meets their needs, is affordable for their families, and offers networks of pediatric providers. In 2016, the number of uninsured children was the lowest it has ever been – 3.6 million. Now, we’re back to 4.4 million uninsured kids. In 2019 alone, 320,000 kids lost coverage, and 726,000 have lost insurance since President Trump took office. Almost 200,000 children under the age of six have lost coverage. These numbers — it should be noted — are pre-pandemic.

Twenty-nine states went backward in the rate and/or number of uninsured kids. New York is the only state that showed a slight improvement. The states with the biggest increases, of more than 1.5 percentage points, are South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Arkansas, Missouri, Delaware, Arizona, and South Carolina. States that saw increases of more than 20,000 uninsured children during the three-year period include Illinois, California, Arizona, North Carolina, Ohio, Missouri, Utah, Tennessee, and Indiana. These losses in coverage threaten the health and educational outcomes of children for years to come.

Texas has the largest number of uninsured kids, with nearly one million without coverage. What do advocates recommend to reverse this trend and get more kids covered? Melissa McChesney, Senior Policy Analyst at Every Texan, said via email,

“Texas once again has the worst uninsured rate for children, and our numbers have gotten much worse since 2016. There are two state health policy decisions that could make a huge difference, and we hope Texans will demand action from our leaders. First, process barriers to enrolling and renewing kids’ coverage are cutting eligible kids off the rolls, and that can easily be fixed. Second, but no less important, we have a roadmap for our state and local governments to step up and reverse the campaign of fear that has driven families of kids with an immigrant parent — more than one-in-four Texas children — to drop their Medicaid and CHIP health coverage.”

Latino children have the highest uninsured rates with widespread coverage losses.

The rise in uninsurance for Latino kids has been overwhelming and the gains made over the last decade have been eradicated. With high uninsured rates during a pandemic, Latino children and children of color, who are disproportionately impacted by the health and economic consequence of COVID-19, are at even more risk. Along with the rise in uninsurance for Latino children, the report shows that the poorest children — those living in families with incomes below 138 percent of the federal poverty level — had the largest jump in uninsurance with their rates increasing almost a percentage point from 6.8 percent to 7.7 percent between 2017 and 2019. The youngest kids, those under age six, experienced an increase in their uninsured rate from 3.8 percent to 4.7 percent over the three-year period.

The lack of health coverage for these young children is particularly alarming because this population requires frequent well-child exams during these years. Not only do they need timely vaccinations, but they also need their height, weight, vision, and hearing checked. Developmental screenings that can determine a need for early interventions are routine during those first years and occur at well-child visits. All of these can be missed when children go without coverage.

What can state and federal policymakers do? Let’s start with these steps: Renew our national commitment to cover children and their families. Commit to children receiving continuous, affordable, uninterrupted coverage that meets their needs. Undo the public charge rule and create a campaign that welcomes children into coverage through Medicaid and CHIP. Give children every opportunity to get the health coverage and care they need to grow and develop. Invest in the health of children today and for their futures.