Around the time of the U.S. Surgeon General’s report alerting the country to the crisis in mental health for American children, teens, and young adults in December 2021, there was a collective awakening about the magnitude of this problem. Suicide rates were climbing, teens were showing up with behavioral health issues in emergency rooms at alarming rates, and teens and high numbers of young adults reported that they were “not OK.” Nearly every news article on the mental health crisis for our children and teens reported dire statistics while also noting that this problem was brewing well before the pandemic. The public and Congress seemed to finally recognize that mental health is an important part of one’s overall health. Mental and physical health are inextricably linked.

Thanks in large part to significant media coverage, more people are now aware that our health care system isn’t equipped to handle the volume of mental health issues facing our children and youth. While parents expect that a child should immediately see a doctor when they have a broken leg, a seizure, or suffer a serious asthma attack, children who suffer from a mental health disorder must often wait weeks or months to receive treatment – if at all. In fact, typically, 11 years pass between when the first symptoms appear and when treatment begins.

Mental illness impacts everyone — rich or poor, urban or rural, young or old, and individuals of all races, sexual orientations, and gender identities. Between 2007 and 2017, the suicide rate for Black children rose from 2.55 per 100,000 to 4.82 per 100,000, and suicide attempts are rising faster among Black youth than any other racial or ethnic group. More than 40% of youth who identify as LGBTQ+ including more than half of all transgender youth say they have seriously considered suicide in the last year.

At this time of highly partisan political debates, we remain hopeful that lawmakers will continue to make progress. We saw cooperation during the winter and spring of 2022 when, on a bipartisan and bicameral basis, House and Senate committees with jurisdiction over Medicaid, health care and children’s issues began holding hearings on the state of mental health of America’s children and youth. Academic experts testified about the severity of the youth mental health crisis. Medical experts shared their perspectives on the crisis and lamented that we do not have enough professionals in the workforce pipeline to meet the demands for services. Both groups offered suggestions to improve access to services and increase the workforce, but their solutions come with large price tags and long time frames in which to recruit, train, and educate more mental health professionals.

Several House and Senate hearings included teenagers as part of their witness panels. The teens told their stories and offered suggestions for what can be done – what needs to be done. The teens who told their stories were compelling witnesses because they shared their lived experiences with Congress. Senators and House Representatives listened attentively as teens spoke from their hearts. The teen witnesses did not represent professional medical associations, hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, social service agencies, academic institutions or think tanks. Rather, they were articulate, passionate, young people, sharing their personal stories of mental health challenges and offering their policy solutions for the greater good of children, teens, and young adults across the country. Some teens spoke about their volunteer experiences in high schools helping other teens find comfort and support. Other teens told of their volunteer work on peer-to-peer support lines (phone/text/chat) to answer calls from youth in crisis. House members and Senators were visibly moved by the teens’ testimonies and complimented the youth witnesses, thanking them for being brave and sharing their personal stories and experiences before a Congressional committee and on C-SPAN. But the real turning point in these hearings was when several Senators and House Members acknowledged that Congress should listen more frequently to teens when trying to develop mental health policy solutions for them. As one teen eloquently said, “nothing for us without us.”

All of the teen witnesses offered common-sense recommendations for what needs to be done to bring more awareness of mental health issues in schools and communities. They spoke of the need for downstream efforts in schools and communities to help children learn coping skills when anxiety and challenges arise. They spoke of the need for prevention efforts, removing stigma, and early intervention as ways to prevent mental health from declining in the first place.

By early spring of 2022, momentum was building in Congress to draft legislation to address the needs of children and youth. Then, the horrific Uvalde shooting in Texas (where 19 children and 2 teachers were killed) occurred on May 24th which was the catalyst for Congress to address gun violence and provide more mental health support to children and youth. Congress passed the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act (BSCA) in July of 2022. The legislation increased funding for many health-related programs, including community-based behavioral health clinics, increasing awards to train primary care residents in the prevention, treatment, and referral of services for children and adolescents, and funding to promote the integration of behavioral health into pediatric primary care by supporting pediatric mental health care telehealth access programs. Congress made a significant investment in building awareness of and access to mental health services in schools. Another important piece of BSCA was increased funding to enhance the 988 National Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. And yet, despite significant monetary investments made in BSCA, the funding still falls short of meeting the high demand for mental health services.

Simply stated, there is a workforce shortage. Parents are having difficulty finding licensed, clinical professionals to see their children in a timely manner. Oftentimes, they must wait weeks or months to see a provider. “Ghost networks” are truly scary to parents who comb through their insurance carrier’s network provider directory only to find that these professionals are no longer taking new patients or have very long waiting lists. Schools are finding it difficult to hire mental health professionals to work in the schools full-time. Schools also find it challenging to hire enough mental health professionals in the community to work on a part-time, contract basis in order to help the schools meet the rising demand for services. The human cost of this workforce shortage will result in more suicides, more attempted suicides, students who are unable to learn in school due to mental health issues, youth who lose interest in social activities, and parents and family members who suffer the physical, emotional, and financial costs of not being able to find care for their children in crisis.

Overwhelming Public Support for Additional Mental Health Resources

According to a poll conducted by Lake Research Partners in May 2022 for First Focus on Children, American voters believe — by a roughly 6-to-1 margin — that the federal government is spending too little on the health, safety, and well-being of our children. Support for children’s programs crosses race, gender, and party lines. By a 66-9% margin, voters believe that we are spending too little rather than too much on accessing mental health services for children.

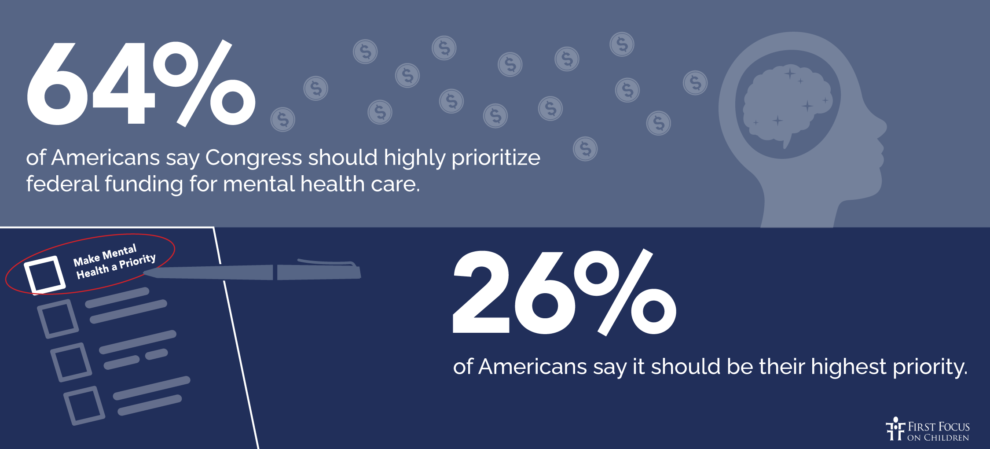

A recent survey by the National Alliance of Mental Illness found that there is widespread support for Congress to do more regarding mental health. Some highlights of the report include:

Strong widespread agreement that mental health is just as important as physical health.

93% of Americans agree mental health is just as important as physical health, and 72% strongly agree.

The majority of Americans, regardless of party affiliation, say Congress has done too little to address the current state of mental health care nationwide.

More than half say federal funding for mental health care, the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, and suicide prevention programs should be high priorities for Congress to address.

Three in five (61%) Americans say Congress has done too little to address the current state of mental health care.

64% of Americans say Congress should highly prioritize federal funding for mental health care, and 26% say it should be their highest priority.

The vast majority of Americans agree that mental health crisis services should be available to everyone, not just to those who can pay out-of-pocket. Most also support expanding coverage of mental health care via health insurers.

Ninety-one percent say all health insurance should cover mental health crisis services. The majority of Americans, regardless of party affiliation, agree, including 95% of Democrats and 89% of both independents and Republicans.

About nine in ten Americans agree mental health crisis services should be available to everyone, not just to people who can pay out-of-pocket, and that insurers should cover mental health care services the same way they cover physical health services (91% and 90%, respectively). Here, too, there is strong bipartisan agreement.

Assess and Rebalance the Pipeline of Mental Health Professionals to Treat Children and Youth

With strong public support and bipartisan consensus that more must be done, there is reason for optimism that Congress and the Administration will continue to shine a light on this nationwide problem and make wise investments in our children’s mental health. Once we know how much is spent overall to train pediatric mental health professionals, which types of professionals are being trained, and how many professionals we are paying to train each year, Congress can better assess the situation and make informed decisions about how to provide for the mental health needs of American children, youth and young adults.

Discussions with Congressional staff, however, seem to indicate that there is no single document or data source that lists all federal funding spent on mental health workforce development, much less on pediatric mental health workforce development. If mental health is indeed a high priority issue for both the House and Senate, information about spending levels should be more readily available. Congress and the Department of Health and Human Services should provide leadership on improving access to the data.

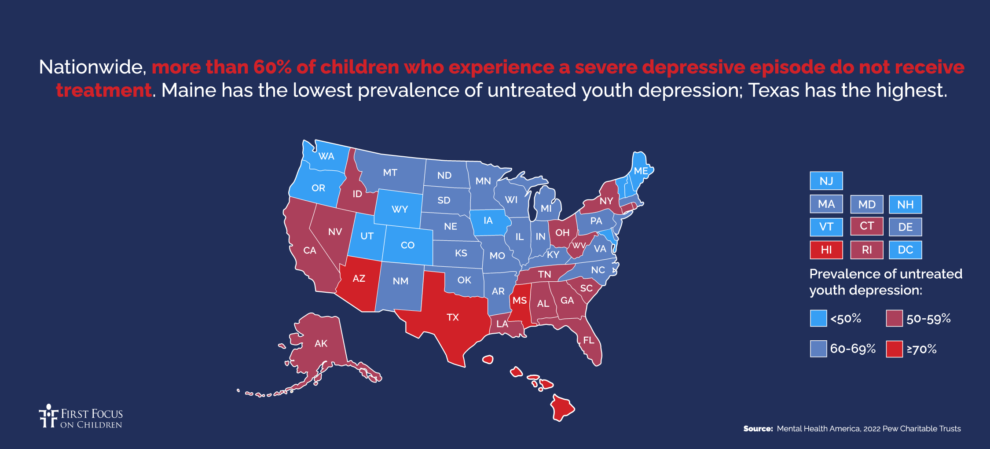

We must methodically and carefully determine what types of services are needed – and where. A heat map produced by Mental Health America in 2022 shows that more than 60% of children who experience a severe depressive episode do not receive treatment. Certain states offer less care than others. Professional organizations that represent mental health providers gather state and local data to show where their medical professionals are located. Pulling this data together will help identify where there are large numbers of practitioners, where there are moderate numbers, where there are a few – and where there are none. We know for sure that large pockets of need exist in our country. Rural areas are especially lacking in resources, but the situation is so severe that shortages exist across the country. Ideally, a heat map could be created showing the concentrations of all pediatric mental health professionals in states and counties.

Considering the flurry of congressional hearings on youth and mental health in the past two years, fiery speeches on the need to do more for our children, and the newfound desire to involve youth in policy solutions, it makes sense to wonder whether Congress realizes the inadequacy of the pediatric mental health workforce funding levels. Does Congress know and not care? Or does Congress not know? Most likely, Congress doesn’t know and would be appalled if they knew how few federal dollars are allocated for pediatric mental health workforce training at a time when we have a youth mental health crisis in our country.

Some Preliminary Numbers

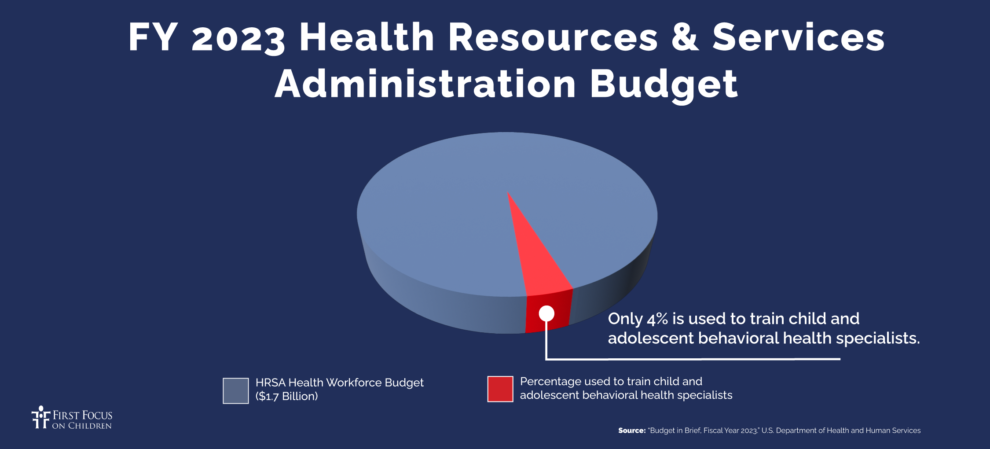

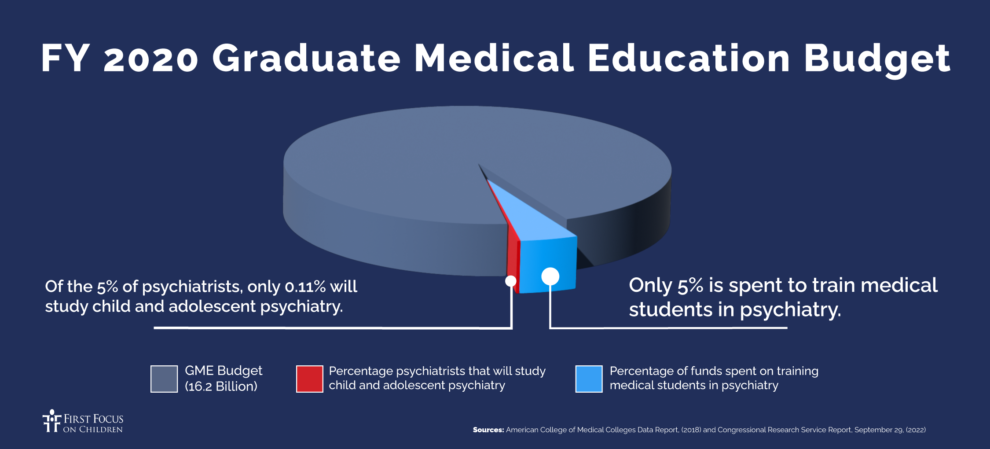

In the absence of a list of pediatric mental health federal workforce programs, it makes sense to look at two of the more important health care workforce programs that provide health care training. First, the U.S. spends approximately $16.2 billion a year on developing the Graduate Medical Education (GME) workforce. GME is the backbone of our country’s training program for health care and behavioral health care professionals. Of all the students in the GME pipeline, fewer than 5% of students are pursuing psychiatry: Of those students, well under 1% – just 0.11% are pursuing child and adolescent psychiatry. The second federal program that makes investments in the health care workforce is the Health Resources and Service Administration (HRSA). Of HRSA’s Health Workforce budget of $1.7 billion, only 9.4% is allocated to the behavioral health workforce. Of that amount, just 4% is allocated to training for child and adolescent behavioral health.

There are likely a few smaller, federal programs that allocate some funding for pediatric mental health training, but GME and HRSA are the largest. Based on those numbers, our country is woefully underinvesting in pediatric behavioral health. Less than 1% of all GME dollars are spent to train child and adolescent psychiatrists. That number alone should sound some alarms in Congress. Similarly, only 4% of HRSA dollars are spent to train child and adolescent behavioral health professionals.

While psychiatrists and psychologists are required to have the highest levels of education to treat children and youth, it is prudent to make investments in growing a range of pediatric mental health care providers, such as licensed clinical social workers, licensed professional counselors, and nurse psychotherapists. These professionals are more likely than psychiatrists to provide services in schools and community clinics. What can be done to grow the number of these professionals? The more we can grow services at the community level, the less children and youth will end up in hospital emergency rooms or in residential treatment centers out-of-state.

Other Non-Clinical Options

Simply adding more funding to train and educate various pediatric mental health professionals is not all that is required. Congress must address parity issues with private insurance and Medicaid. Reimbursement rates for mental health providers are lower than for comparable physical health, and Medicaid billing challenges exist. Some psychiatrists and psychologists come out of school and only see private-pay patients. How can they be incentivized to see children and youth from lower- and middle-income families? We must create a structure that will work best for America’s youth, while Congress simultaneously tackles ghost networks, parity, billing, and other issues.

Congress can do several things right now to get more help to youth more quickly. Non-clinical, mental health resource options are less costly, more immediate, and highly effective. For instance, increasing the number of youth peer support specialists (teens and young adults with “lived experience”) who work one-on-one with teens has proven very effective. Young people who receive peer support cite improvements in self-esteem, self-efficacy, and recovery from mental health conditions. Care can be delivered via call center programs such as YouthLine in Oregon where teens can call/text/chat with peers (who have been trained and are under clinical supervision), via mobile crisis units that respond to 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline calls, and in schools and communities.

We can also better align the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline so that it expands interventions such as texts, and other digital modes of communication that focus outreach on youth, teens, and young adults. Integrating training across contact centers about the benefits of youth peer support services within the 988 Lifeline network and coordinated referrals to peer-run support lines such as Youthline will expand the reach and use of the 988 Lifeline by teens and young adults.

Call to Action

We urge Congress and the Department of Health and Human Services to commit to eliminating “mental health care deserts” and ensuring that all children, whether they live in urban or rural areas, have easy access to care. We must gather and share data, determine current funding levels, and make budgetary decisions based on our current resources and the demand for services. We must design a continuum of care that offers preventive services, reduces the stigma surrounding mental health treatment, and breaks down barriers between programs. Policymakers, clinicians, non-clinicians, advocacy organizations, and the children and teens who will use these services must participate in building an effective model. Time is of the essence. Our children cannot wait.

Written by Elaine Dalpiaz, Vice President for Health Systems and Strategic Partnerships & Averi Pakulis, Vice President for Early Childhood and Public Health Policy