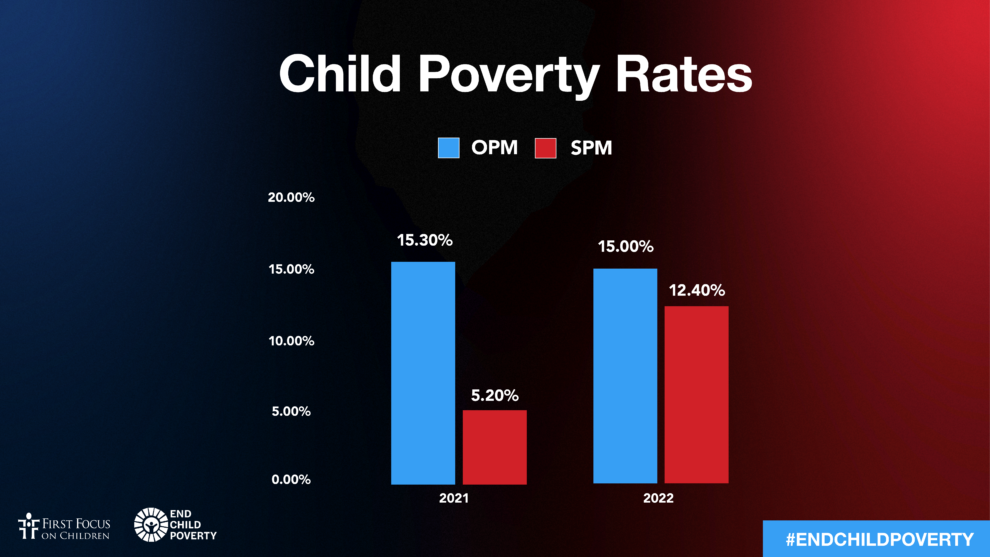

On September 12, 2023, the U.S. Census Bureau reported that the United States saw a significant increase in child poverty, with 12.4 percent of children (nearly 9 million children) living in poverty in 2022 compared with 5.2% of children (3.8 million) in 2021.

This represents a more than doubling of child poverty in 2022 from 2021 — a record one-year increase and significant backtracking from progress made in 2021.

The increase in child poverty in 2022 is unacceptable. Our past progress shows that child poverty is a policy choice — we know how to reduce child poverty when our country’s lawmakers have the political will to act.

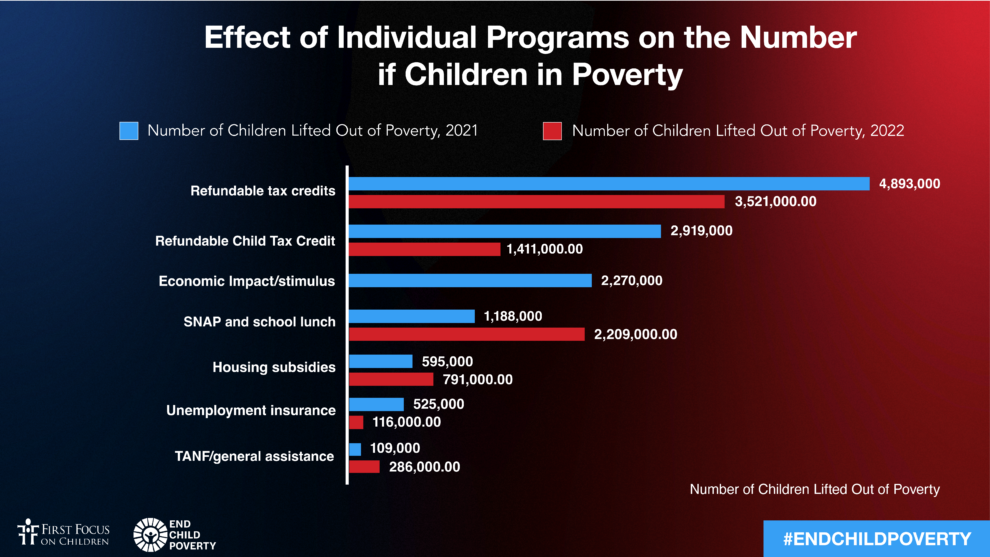

This historic one-year increase in child poverty in 2022 is due largely to the expiration of improvements to the Child Tax Credit included in the American Rescue Plan Act, which in 2021 had prevented nearly 3 million children from experiencing poverty. The termination of other assistance in 2022, such as the third round of Economic Impact Payments, as well as the ending of expansions to the Unemployment Insurance program also contributed to the increase in child poverty.

Increases to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits were critical in helping to reduce food insecurity and mitigate the increase in child poverty in 2022. The program alone lifted 1.4 million children out of poverty and lifted a total of 2.2 million children out of poverty when combined with increased school meal benefits. However, these benefits were not enough to overcome the impact of the expiration of several forms of cash assistance or to combat the high cost of food, rent, and other goods.

Poverty has Significant Implications for Our Children and Our Country

The increase in child poverty in 2022 is unacceptable. The progress made in 2021 proved that child poverty is a policy choice — and one that is entirely preventable when our country’s lawmakers have the political will to act. Poverty, even for a short time, can have significant negative implications for children’s development and future success. Poverty means less income in households for a plentiful amount of nutritious food, safe shelter, proper physical and mental healthcare, clean diapers, education materials, and other materials that are critical to a child’s healthy development. Poverty means increased stress for parents and caretakers, reducing their mental and emotional bandwidth for their children as they struggle to try to make ends meet for their household.

Poverty is linked to worse physical health outcomes for children, including chronic diseases such as asthma. Children living in poverty are at higher risk of experiencing food insecurity, which negatively impacts their growth and development. This contributes to a lack of school readiness, and poor children obtain lower levels of educational attainment and earn less as adults when compared to their non-poor peers. The duration of poverty matters for children — the longer a child experiences poverty, the greater the likelihood they will experience poverty as an adult.

Poor families with children are more likely to come into contact with the child welfare system. Reporters of child maltreatment too often conflate poverty with neglect due to misunderstanding or bias, and therefore report neglect when the real issue is poverty and lack of resources. Child Trends reports that nearly half of states do not specifically exempt poverty-induced deprivation from their definitions of child maltreatment, which makes children from poor families in these states more susceptible to being reported, investigated, and substantiated for child neglect.

Poverty doesn’t just have negative implications for individual children, but for our society as a whole, costing our country upwards of $1 trillion a year in lost economic output.

We Must Act to End Child Poverty in the United States

The good news is, we know what works to combat child poverty. A 2019 non-partisan, landmark study from the National Academy of Sciences confirms that the negative outcomes associated with child poverty directly result from a lack of income, and that when families receive cash assistance, it not only reduces child poverty but also improves children’s short-and long-term health, educational, and economic outcomes, both by increasing access to resources that support children’s healthy development as well as reducing household stress. Cash assistance has a two-generation effect in promoting economic mobility: In addition to supporting children, the assistance helps adults in the household afford child care, transportation to work, higher education, or job training programs that lead to steady employment and higher-paying jobs.

The outcomes from the 2021 expansions to the Child Tax Credit confirm these findings. Numerous surveys found that households with children reported using the payments to buy food, pay rent, cover child care costs, and provide clothing, educational materials, and activities that enrich children’s lives in the short- and long-term. Child poverty was nearly cut in half, and food insufficiency among families with children (households that reported that they sometimes or often do not have enough to eat) decreased by over 25%. Families reported that the payments gave them a sense of relief from the constant worry of how to cover bills and keep their household afloat.

It is critical that we act to not only regain the progress we made in reducing child poverty in 2021, but work to ensure that every child has the resources to thrive.

How We Can Take Action

We must start with a true understanding of just how many children are experiencing material hardship in the United States. Income thresholds used to measure poverty remain much too low, so many households with children with incomes that greatly exceed the poverty line still experience significant financial insecurity and hardship. There are existing tools that show us that families, even those in areas with a lower cost of living, need to earn much more than twice the poverty line (which in 2022 was $31,453 for a family of four with two children) for an adequate standard of living. It is critical that we improve upon existing poverty measures to more accurately reflect household material hardship and deprivation and include children in the U.S. territories.

We must also work to advance racial equity. Even with the progress made in 2021, significant racial and ethnic economic disparities still persisted, and now in 2022, the poverty gap widened between Black and Hispanic children compared to white children. Children in immigrant families continue to face more significant barriers to economic stability than non-immigrant families due to restricted access to tax credits and other benefits. The Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) data released for 2022 does not consider children in Puerto Rico and the other U.S. territories but figures show they face higher rates of poverty than children in the 50 states and the District of Columbia due to their unequal access to federal benefits as part of a long history of racism and discrimination against Americans living in the territories.

While we have the evidence as to what works to combat child poverty, our country has lacked the political will necessary to make lasting progress. Setting a national child poverty reduction target in the United States provides a tool for advocates, the media, and voters to hold lawmakers accountable to making child poverty reduction a top priority. Other countries have proven the effectiveness of poverty reduction targets — the United Kingdom cut its child poverty rate in half between 1999 and 2008 after setting a child poverty reduction target, and before the outbreak of COVID-19, Canada had reduced child poverty by more than a third since 2015. In the United States, momentum is growing, with child poverty reduction targets established in California, and most recently in Puerto Rico and New York state.

Setting a target will help create the momentum needed to pass long-term policies and investments needed to ultimately end child poverty in the United States, such as a permanent monthly child allowance and reforms to the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program that would increase cash assistance to low-income families.

Annual Census Data for 2022

Supplemental Poverty Measure

The SPM is the most realistic measure of annual poverty, using a household income threshold based on the cost of food, clothing, shelter, utilities, and a small number of other needs, and adjusts this figure for family size and geographic differences in housing costs. The census then considers cash income (including child support), in-kind benefits, minus taxes (or plus tax credits), work expenses, out-of-pocket medical expenses, and child support paid to another household.

Using the SPM, which considers the impact of the Child Tax Credit and other critical assistance provided for households with children, 12.4% of children (nearly 9 million) lived in poverty in 2022 compared to 5.2% (3.8 million) in 2021.

This means the child poverty rate more than doubled — a 138% increase — in just one year, resulting in an additional 5 million children experiencing poverty in 2022.

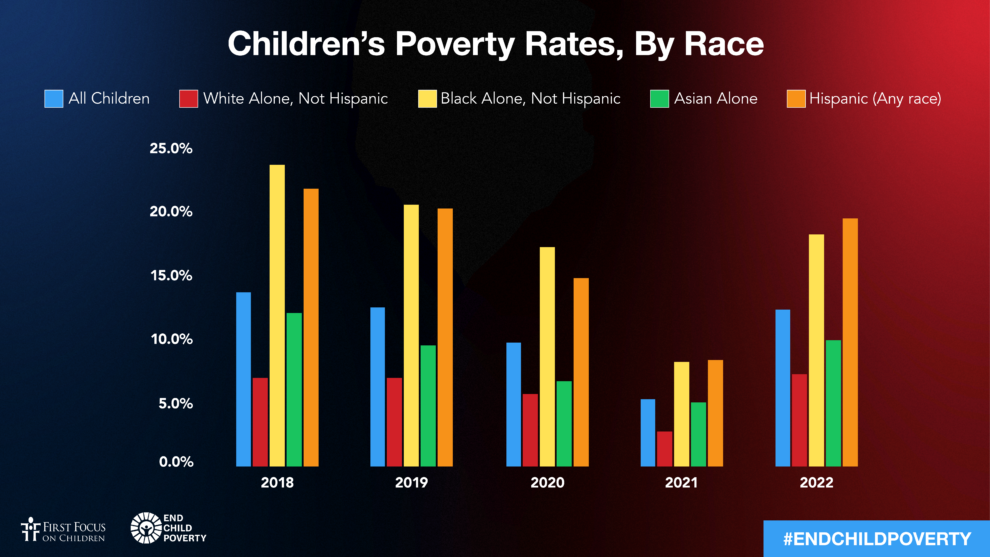

- Following the expiration of improvements to the Child Tax Credit, racial disparities widened and and in 2022, Black and Hispanic children experienced poverty at a rate more than twice that of white children:

- Black children (alone, not Hispanic): 18.3%

- Hispanic children (any race): 19.5%

- White (alone, not Hispanic): 7.2%

- American Indian and Alaska Native (alone): 25.9%

- Asian (alone): 9.9%

- null

- Nearly 3.3% of children (over 1 million) were living in deep poverty. This is more than double (a 135% increase) from 2021. These are children in households with very few resources (an annual income of less than $16,000 a year for a family of four with two children) who face severe deprivation.

- 12.9% of children under 6 were living in poverty in 2022, experiencing a lack of resources while their brains are undergoing critical stages of development.

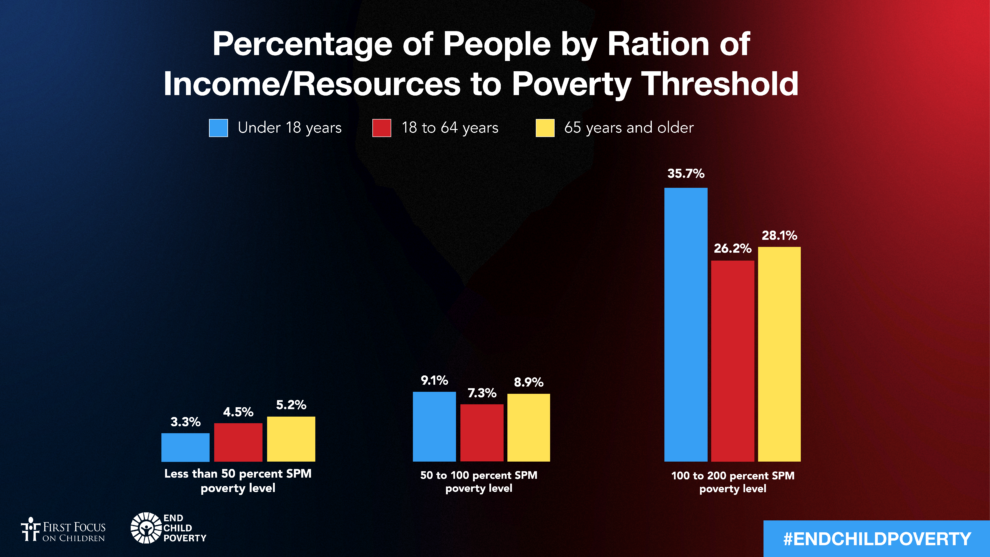

- 35.7% of children (over 25 million) were living in households with annual incomes up to double the poverty threshold — around $60,000 a year for a family of four with two children — but were still struggling with material hardship.

- Using the Economic Policy Institute’s Family Budget Calculator, a family of four with two children needs at least an annual income of over $80,000 a year in most areas to have an adequate, but modest, standard of living.

Below are government programs included in the SPM and the number of children lifted out of poverty because of each program.*

*Note that these numbers reflect the expiration of expansions to the Child Tax Credit, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and Unemployment Insurance, as well as the termination of the third round of Economic Impact Payments in 2022.

The Impact of the Expiration of Improvements to the Child Tax Credit

In 2021, the Child Tax Credit alone lifted nearly 3 million children out of poverty. Due to the expiration of improvements made to the Child Tax Credit in the American Rescue Plan Act, in 2022 the Child Tax Credit still had an significant impact but only lifted half as many children — 1.4 million — out of poverty. Columbia University’s Center on Poverty and Social Policy finds that if the improvements to the Child Tax Credit continued in 2022, the child poverty rate would be over 4 percentage points lower, sparing 3 million children from experiencing poverty.

While significant disparities still existed, improvements to the Child Tax Credit had narrowed the racial child poverty gap by reaching many Black and Hispanic children that were previously left out of receiving some or all of the Child Tax Credit because their families earned too little to be eligible. That gap widened once again in 2022, as the Child Tax Credit reverted back to previous law which leaves out one-third of all children from receiving the full credit, with Black and Hispanic children disproportionately left behind.

Children in immigrant families continue to face higher rates of poverty than their nonimmigrant peers because they face more significant barriers to economic stability than nonimmigrant families due to restricted access to tax credits and other benefits. For example, an estimated 1 million immigrant children without Social Security numbers have been unfairly excluded from receiving the Child Tax Credit since 2018. Other immigrant households have been unable to access the Child Tax Credit because of delays in filing and receiving Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITINs), and some may avoid filing altogether for fear of negative implications to their immigrant status.

Children in Puerto Rico and the other U.S. territories are not accounted for in the Supplemental Poverty Measure, but available data shows that they continue to experience poverty rates nearly 4 times higher than children in the 50 states. Improvements to the Child Tax Credit made in the American Rescue Plan Act included a permanent expansion to allow families of all sizes in Puerto Rico to be eligible. (Previously, only families with three or more children were eligible, leaving out 90 percent of families on the island.) Families in Puerto Rico, however, were not eligible to receive the advanced monthly payments, and efforts are still ongoing to help eligible families in Puerto Rico file for the credit.

Official Poverty Measure

The Official Poverty Measure (OPM) represents the share of children in the United States under age 18 who live in families with incomes below the federal poverty level, which is used to determine eligibility for many public assistance and means-tested federal programs. The OPM only accounts for pre-tax cash income and uses a federal poverty definition that consists of a series of thresholds based on family size and composition. In 2021, poverty under the OPM was defined as annual income below $29,678 for a family of four with two children, while extreme poverty was defined as less than $14,839 per year.

The OPM shows that without the impact of tax credits, such as the Child Tax Credit, and inkind benefits, child poverty was higher in 2022, at 14.9% compared to 12.4% under the SPM, representing an additional 2 million children experiencing poverty under the OPM. The OPM did not see a significant statistical change from last year for children.