This paper is part of First Focus on Children’s upcoming series Big Ideas 2022: The American South

Forward

This report was written before the Supreme Court overturned the constitutional right to abortion in Dobbs v. Jackson Whole Women’s Health. Many of the same states whose cash assistance policies this report describes as reflecting racist and sexist policy histories are also those that have banned or severely restricted abortion access or are trying to do so. These new restrictions, legal and financial, will fall hardest on the people with the fewest resources — disproportionately people of color, immigrants, and others who have historically been marginalized. They will face the highest hurdles to overcoming state-level restrictions due to this nation’s long history of racism and discrimination. In states with serious restrictions to abortion access, people who are pregnant will have less personal autonomy. Many people who have low incomes, little savings, inflexible jobs, or child care responsibilities will face enormous obstacles, financial and otherwise, if they decide to seek abortion care in another state or if they are compelled to carry pregnancies to term that they would have chosen to terminate if abortion was accessible in their communities.

Being denied abortion harms families’ long-term financial well-being, the groundbreaking Turn Away Study has found.[1] Women — the study did not include trans men and non-binary people seeking abortions — who were denied an abortion because they were past a state’s gestational limit were four times as likely to have incomes below the poverty line and are less likely to be able to afford basic necessities like food and housing.

All people should be able to decide whether or not to have children and to have those decisions supported by public policies that equip them to succeed. This includes both ready and affordable access to abortion care for those who make the decision to terminate their pregnancies and adequate supports for families with low incomes who decide to carry their pregnancies to term. For those who choose to have children, monthly cash assistance and employment supports, both of which Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) is supposed to provide, should be available and robust enough to support families and children. However, as this report illustrates, TANF — rooted in more than a century of racism and sexism, primarily targeted at Black women but with harmful effects for all families with children who need help — falls far short of what families need.

Many of the same analysts and policymakers who have championed these racist TANF policies are also behind policies to restrict abortion access. Already, abortion is either completely banned or severely restricted in Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Idaho, Louisiana, Kentucky, Missouri, Mississippi, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas, and more states are expected to follow suit.[2] In most of these states, TANF reaches fewer than 10 out of every 100 families living in poverty and provides a maximum benefit level below 20% of the poverty line.

With more families likely to need financial assistance due to abortion bans, whether or not TANF meets this need will be another chapter in a longer story of cash programs’ interaction with Black and unmarried women’s reproductive lives. Under TANF’s predecessor, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), states instituted “suitable home” policies that denied assistance to families with a child born to an unwed mother and searched the homes of recipient families for any man living in the home under suspicion that they were a father or “substitute” father not providing for the children. Several states considered (but did not implement) sterilization of unwed mothers on AFDC and, later, birth control requirements as a condition for AFDC receipt. In the 1990s, almost half of U.S. states adopted family cap policies, which deny families more cash assistance when they have another child while receiving TANF. Family cap policies still exist in 11 states, a majority of which have restricted or banned abortion. Many of these policies targeted Black and unmarried mothers or were enacted in states with high Black populations.

Providing access to the full range of reproductive health services, including abortion, and ensuring that families have the support they need to meet their basic needs are fundamental for achieving reproductive justice. While some who celebrate the Dobbs decision have proposed strengthening economic support programs, including TANF, doing so is not a substitute for abortion access and bodily autonomy.

As the Reproductive Justice framework,[3] developed by a group of Black women in 1994, illustrates, access to reproductive health services including abortion and economic support programs like TANF are complementary to each other: together, both sets of policies provide people with dignity and autonomy over their bodies and lives by enabling them to make the decisions best for themselves and their families.

Undoing the Racist Legacy of Cash Assistance in the South: Reimagining TANF Using the “Black Women Best” Framework

Economic security programs can help families meet basic needs and improve their lives, but design features influenced by anti-Black racism and sexism have created an inadequate system of support that particularly harms Black families and other families of color. This is especially true in the South, which has a long legacy of denying or providing limited cash support to families in need. Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the nation’s primary program for providing cash assistance to families with children when parents are out of work or have very low income, is perhaps the clearest example of a program whose history is steeped in racist ideas and policies that particularly strip Black women of their dignity. Those policies do not solely harm Black families; they harm all families. If TANF programs remain in their current diminished state, millions of children — disproportionately Black children — will be left behind to experience the detrimental impacts of poverty.

A large and growing body of research shows that experiencing poverty and hardship, even briefly, can have detrimental, lifelong impacts on children. Researchers have linked stress caused by a scarcity of resources to long-lasting negative consequences for children’s brain development and physical health.[1] People who experience poverty in childhood have lower levels of educational attainment, lower earnings, higher likelihood of being arrested, and poorer health in adulthood, a 2019 National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine report found.[2]

Congress created TANF in 1996 to replace Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), purportedly to help families lift themselves out of poverty through work. But much of the debate around the 1996 law was centered (often implicitly, but sometimes explicitly) on criticisms of Black mothers,[3] who were portrayed as needing a “stick” to compel them to be more responsible and leave the program. TANF’s harsh work requirements and arbitrary time limits disproportionally cut off Black families and other families of color. Also, Black children are more likely than white children to live in states where TANF has the lowest benefits and reaches the fewest families in poverty. In the decade after policymakers remade the cash assistance system, it became much less effective at protecting children from deep poverty — that is, at lifting their incomes above half of the poverty line, a little more than $900 a month for a family of three — and children’s deep poverty rose, particularly among Black and Hispanic children.[4]

Many of TANF’s rules mirror those dating back to cash programs of the early 20th century, and many of its assumptions reflect anti-Black racism dating back to enslavement. Throughout the history of cash assistance, many policymakers and public figures have used these same racist justifications and stereotypes to question Black women’s reproductive choices; coerce Black women to work in exploitative conditions; and control, deride, and punish Black women who receive cash assistance. TANF’s design perpetuated these attitudes and, in some ways, reinforced them, such as through stricter work requirements and expanded state control over program rules.

This paper, an abridged version of a report published by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities in August 2021,[5] applies the “Black Women Best” framework to reimagining TANF. Developed by Janelle Jones, former chief economist at the Department of Labor, the framework “argues if Black women — who, since our nation’s founding, have been among the most excluded and exploited by the rules that structure our society — can one day thrive in the economy, then it must finally be working for everyone.”[6] Consistent with Jones’ framework, redesigning TANF so that it centers the needs of Black women and families would better serve families of all races and ethnicities by adequately helping families struggling to afford the basics and offering meaningful opportunities to gain skills and secure quality jobs.

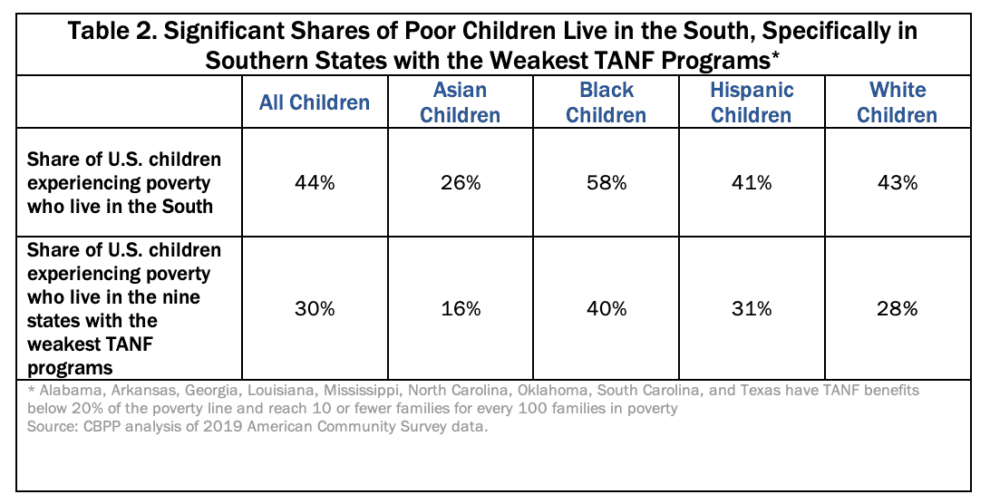

This paper focuses on the South, where many of the policies and trends discussed originated and are often most harmful. Children and their families in Southern states face higher levels of poverty and economic hardship than those in other states. Four in 10 of the nation’s children who experience poverty live in the South (as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau), a higher share than the Midwest, Northeast, or West.[7] Furthermore, 58% of the nation’s Black children who experience poverty live in the South, as do 43% of white children, 41% of Hispanic children, and 26% of Asian children who experience poverty.[8]However, state policymakers in the South have largely chosen not to use the policy levers available to reduce the extent and severity of child poverty. The South has weaker labor and social support policies and programs than other regions, a recent report from the Center for American Progress finds. TANF is a prominent example: TANF programs in nearly all Southern states rank among the least generous and most restrictive in the nation.[9]

TANF Benefits Too Low to Support Families, Especially in the South

States’ long-standing control over benefit levels in cash assistance programs set the course for the large geographic and racial disparities in TANF today. As Congress debated the Social Security Act of 1935, which created the Aid to Dependent Children (ADC) program (later renamed Aid to Families with Dependent Children, or AFDC), initial proposals to ensure adequate benefits across the country were undermined by a then-powerful Southern congressional bloc, which insisted on state and local control over the program.[10] Later attempts to establish a minimum federal benefit for AFDC similarly failed in Congress. The defeat of these and other proposals to make cash assistance more adequate and accessible disproportionately harmed Black women and their families and, in turn, helped maintain racial discrimination and segregation in the economy — especially the Southern economy — by ensuring that AFDC did not compete with the extremely low wages paid to Black workers, who often were segregated into agricultural and domestic roles.[11]

States employed different strategies to restrict access to benefits and to keep benefits low, and these efforts often disproportionately affected Black families. Between the mid-1930s and the early 1960s, state ADC/AFDC programs discriminated against Black families most visibly by preventing them from accessing the program in the first place. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, some states sought to prevent Black families from receiving ADC if mothers could work. As a field report from the late 1930s explained:

There is hesitancy on the part of many [officials administering ADC in the South] to advance too rapidly over the thinking of their own communities, which see no reason why the employable Negro mother should not continue her usually sketchy seasonal labor or indefinite domestic service rather than receive a public assistance grant.[12]

As discussed below, “farm policies” coerced mothers to take low-paying jobs by reducing or ending benefits during harvest seasons, and behavioral restrictions attempted to block access to the program altogether. These policies often targeted Black families or arose in states with high concentrations of Black families.

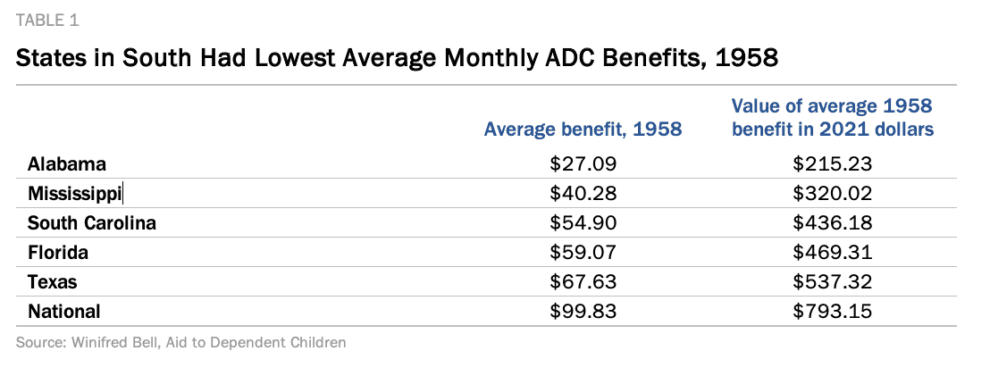

With no federal standard for states to set benefits that met the needs of families, Southern states consistently attempted to keep benefits low. Twenty states set a maximum family grant irrespective of family size by 1958.[13] Fifteen of them were in the South, a region that included half of the country’s Black population.[14] The South was also home to the states with the lowest average ADC benefits in the country as of 1958: Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas. All five states were well below the national average. (See Table 1.)

States maintained full authority to set benefit levels even after the federal government limited states’ ability to add eligibility conditions in the 1960s and 1970s, a move made to root out some particularly problematic eligibility restrictions some states, largely in the South, were imposing. Benefits quickly lost value during the 1970s due to high inflation, and while inflation later moderated, most states did not increase benefits enough to offset the decline.[15] Between 1970 and 1996, maximum AFDC benefit levels lost more than 30% of their value in nearly every state, including every state in the South — a region that generally had lower benefits than the rest of the country when the 1970s began.[16]

Additionally, studies consistently find that between the 1960s and 1990s, states with higher Black populations or higher shares of Black families receiving AFDC had lower average cash benefit levels.[17] This trend was predominant in (but not exclusive to) the South. One study found that between 1982 and 1996, a state’s Black population was a strong predictor of the state’s benefit levels, even after controlling for the state’s ideological leanings: conservative and liberal states with high Black populations had lower average benefits than their peer states with low Black populations.[18]

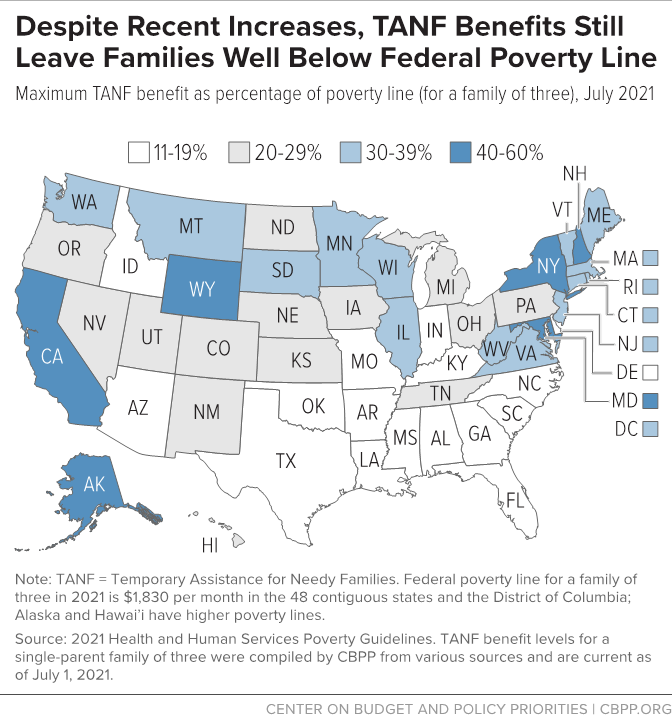

Trends that started in ADC/AFDC have continued throughout TANF’s 25-year history. TANF benefit levels tend to be lower in states where Black residents make up a greater share of the population, even after controlling for other factors, recent research finds.[19] In 2021, 12 of the 16 states with maximum benefit levels below 20% of the federal poverty line were in the South, as were eight of the 16 states that have not increased benefits since TANF’s creation.[20] In those 16 states, benefits have lost more than 40% of their purchasing power due to inflation. For a single-parent family of three, maximum benefit levels in the South range from $204 in Arkansas (11% of poverty) to $727 in Maryland (40% of poverty), with a median of $303 (17% of poverty). Nationally, in comparison, the median maximum TANF benefit level is $498 (27% of poverty), and benefit levels range as high as New Hampshire’s $1,098 (60% of poverty). (See Figure 1.)

TANF’s low benefits leave families without sufficient resources to meet their basic needs. For example, at nearly $100 a month, the cost of diapers for a child takes up a third or more of TANF benefits in most Southern states, leaving less room for other necessities.[21] Some necessities, like modest housing, are practically out of reach for many TANF families, often forcing families into unstable or overcrowded housing arrangements, with some families experiencing homelessness.[22]

TANF Work Requirements Grew Out of Attempts to Control Black Women’s Labor

In the early days of ADC, states had free rein to impose eligibility policies designed to keep certain families off assistance. While these policies did not harm only Black families, they often targeted Black mothers or arose in areas with high concentrations of Black residents. Often these efforts were attempts to keep Black women in low-paid, exploitative jobs. While enslavement had ended decades earlier, the Southern economy remained reliant on cheap labor from a pool of vulnerable Black workers. Restrictive state eligibility policies made coercive jobs under white employers the only option for Black mothers to support their families. For example, a number of states imposed “farm policies,” which reduced or took away assistance for families during the harvest or planting season — often regardless of whether parents actually obtained employment. Louisiana’s 1943 farm policy denied assistance during the cotton-picking season to both newly applying families and those already receiving assistance, nearly all of whom were Black.[23] Similarly, Georgia implemented an “employable mother” policy in 1952 that barred families with earnings from receiving ADC benefits to supplement those earnings. These new rules severely constrained access to ADC in Georgia, disproportionately among Black families.[24][

In the three decades that preceded TANF’s 1996 creation, efforts increased at the federal level to tie AFDC benefits to work. Between the late 1960s and early 1990s, work requirements grew to apply to more AFDC recipients and became more punitive.[25] One of the most consequential developments was the proliferation of “full-family” sanctions as the Clinton Administration granted waivers allowing states to take away benefits from the whole family, including the children, if a parent failed to meet work requirements.

Southern Democrats and other conservative policymakers pushed for these policies as public perceptions of AFDC recipients and people in poverty — two groups increasingly presented as Black in the media — grew more negative.[26] Some policymakers openly acknowledged that their objective was to continue coercing Black people into low-wage jobs. During the congressional debate over President Nixon’s proposed Family Assistance Plan (FAP), which would have replaced AFDC and provided dramatically more aid to Black Southerners, Representative Phillip Landrum of Georgia summarized Southern concerns about FAP by saying that “there’s not going to be anybody left to roll these wheelbarrows or press these shirts.”[27]

Other racialized messaging was more subtle. Claiming that a “culture of poverty” existed in urban centers, conservative intellectuals such as Lawrence Mead and Charles Murray argued for policies that essentially would force low-income Black people to work, regardless of the quality or pay of the jobs available to them.[28]When AFDC caseloads reached record highs in the 1990s, racist arguments blaming Black people for their poverty underpinned some of the calls to “end welfare as we know it,” which became a central campaign pledge of both President Clinton, a Democrat, and congressional Republicans led by Representative Newt Gingrich of Georgia. When President Clinton signed the 1996 bill creating TANF, he claimed it “gives us a chance we haven’t had before to break the cycle of dependency that has existed for millions and millions of our fellow citizens, exiling them from the world of work,” ignoring the structural racism that limited Black women’s employment opportunities.[29]

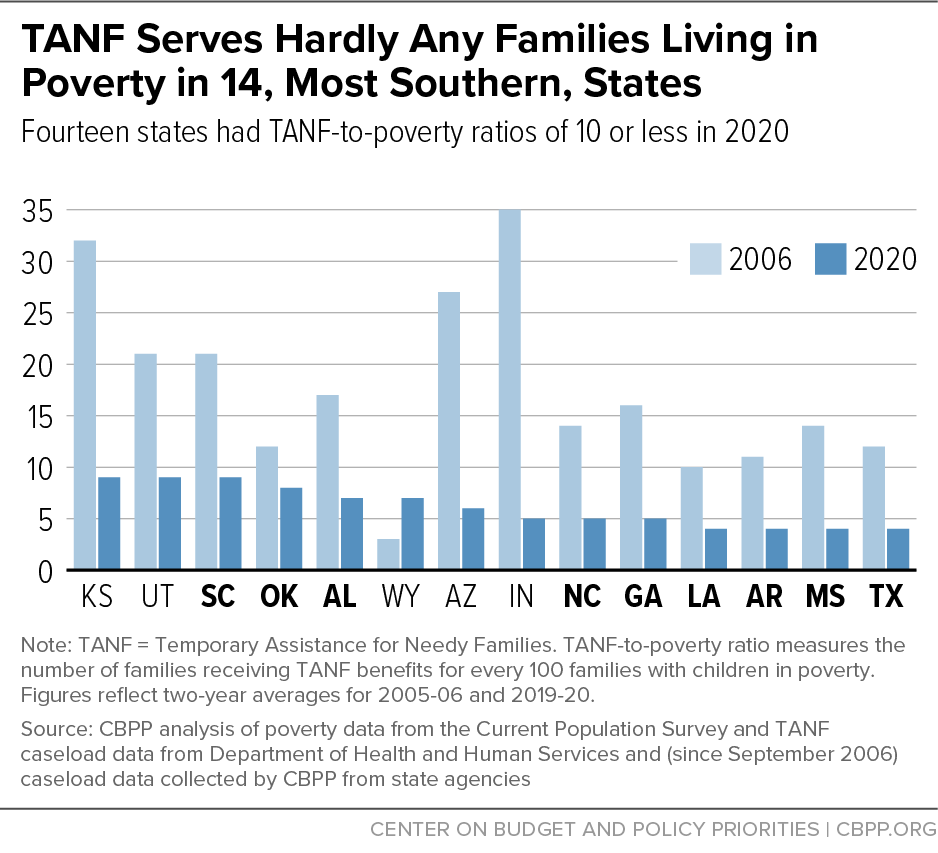

TANF conditioned receipt of cash assistance on work and granted states broad flexibility in creating their work policies and sanctions. States have used this flexibility to implement policies that restrict access to the program, including full-family sanctions and job search as a condition of eligibility. The 1996 law also set a lifetime limit of 60 months on receipt of federally funded benefits, and many states have opted for even shorter time limits, limiting access for many families. Furthermore, TANF created financial incentives for states to reduce caseloads. Because of these and other changes, the number of families TANF serves out of every 100 families in poverty (known as the TANF-to-poverty ratio, or TPR) plummeted from 68 in 1996 to 21 in 2020. [30]

Southern states, which had tended to serve fewer families in AFDC than the rest of the country, have seen access decline to record lows in TANF. Nine of the 15 Southern states had TPRs of 10 or less in 2020 (See Figure 2), and only Delaware and the District of Columbia had TPRs greater than 30. All Southern states have implemented full-family sanctions at some point since 1996, and all but two still take away a family’s whole benefit today.[31]

Figure 2

Policies that take assistance away when people don’t meet a work requirement, which states have made more punitive over time, are a major driver of caseload decline in TANF. TANF programs primarily employ a “work first” approach, which aims to place recipients in jobs as quickly as possible. Such an approach furthers the occupational segregation of recipients, a majority of whom are Black or Hispanic, into low-quality jobs and reinforces the racist stereotype that parents receiving assistance will work only if coerced.

While employment that pays sufficient wages and provides regular hours can be a path from poverty toward financial stability, most TANF recipients are not on that path, a recent analysis of studies of parents leaving TANF shows. In Georgia, for example, 69% of parents who left TANF between 2009 and 2014 worked during their first year after exit, but only 34% were able to work consistently throughout the year,[32] likely because a majority of parents worked in food service and other low-paying jobs that typically offer low job stability.[33] Moreover, only 9% of parents who left TANF earned enough in their first year after exit to lift their families above the poverty line.[34] Among a subsample of the Georgia leavers who participated in more in-depth interviews, 42% were food insecure and 25% experienced homelessness after leaving TANF.[35]

Cash Assistance Policies Sought to Control Mothers’ Reproductive Decisions and Other Conduct

Instead of trusting parents to make the right decisions for their families, TANF is laden with undignified, coercive requirements designed to exclude people due to past conduct rather than current need, and in some cases even to control their reproductive decisions. Similar to work requirements, these policies send a message that parents seeking assistance are irresponsible, criminal, or otherwise undeserving of support.

Efforts to control Black women’s reproductive decisions and other conduct started under enslavement. Enslavers employed forced reproduction to control enslaved Black women while maximizing their economic returns by punishing them when they did not bear children.[36] Even after emancipation, many Black women did not have full control over their sexual and reproductive decisions. Black women and girls were systematically raped by white men in a parallel to the reign of terror in which thousands of Black people were lynched.[37] Cole Blease, governor of South Carolina from 1911 to 1915, pardoned both white and Black men convicted of raping Black women, stating, “I … have very serious doubt as to whether the crime of rape can be committed upon a negro.”[38]

The narratives of promiscuity and irresponsibility that justified Black women’s exploitation under enslavement served as reasons for later cash assistance programs to deny aid to Black mothers. In the late 1940s and 1950s, when Black families and families with divorced or unmarried mothers made up growing proportions of the ADC caseload (as the numbers of white widowed families declined),[39] a number of states started passing laws aimed at “cleaning up” the caseload, as Georgia officials put it.[40]

Several states, for example, imposed “suitable home” policies, which were ostensibly designed to protect children from maltreatment but allowed caseworkers and local administrators to deny aid based on moral determinations of a mother’s fitness for child-rearing. Some 23 states instituted formal suitable home policies, but the most punitive were in the South. These policies often targeted Black families, as these two examples show:

- Florida’s “suitable home” policy equated a mother having a child outside of marriage with child neglect; the family was therefore deemed unsuitable.[41] Officials were likelier to scrutinize Black ADC families than white ones under this definition of neglect. The state threatened to remove children from the home if offending mothers did not release the children to extended family. Yet the state dropped the case if the family withdrew from the program, illustrating that the policy’s real purpose was to remove families from ADC, not to improve children’s well-being. Many families did not even apply to ADC for fear their children could be taken away.[42]

- Louisiana’s 1960 “suitable home” law deemed a family “unsuitable” if it had “illegitimate” children, if the parents were in a common-law marriage (which was more common among Black families),[43] or if the mother was deemed “promiscuous.” Within three months, this law cut off more than 6,000 families (with about 23,000 children) from the program; 95% of the children in those families were Black.

Another set of policies aimed at controlling mothers’ conduct was “substitute father” or “man-in-the-house” rules targeting mothers’ personal relationships. These rules were based on the assumption that if a mother cohabited with a non-disabled man, he should provide financial support to the family even if he had no legal obligation to the child, had little or no income, or in the case of Michigan law, was simply a boarder.[44] These policies often targeted Black families as well. In Dallas County, Alabama, between 1964 and 1967, for example, 182 of the 186 families cut off due to this policy were Black.[45] Several states and localities, including many with high concentrations of Black residents,[46] created special surveillance units to watch mothers’ homes and conducted unannounced home searches, sometimes called “midnight raids,” looking for evidence of a cohabitating man.

A small number of states even considered mandatory sterilization laws for ADC/AFDC recipients in the 1950s and 1960s. Often they cited Black mothers in particular; for example, Mississippi State Representative David H. Glass claimed that “The negro woman, because of child welfare assistance, [is] making it a business, in some cases of giving birth to illegitimate children.”[47] Lawmakers in Illinois, Iowa, Ohio, Tennessee, and Virginia proposed similar policies.[48] Although none of these sterilization proposals was passed into law, many states operated sterilization programs targeting people of color, people in poverty, people with mental illness, and others, some of which continued into the 1970s.[49]

The 1960s and 1970s, a time of significant social change, brought an end to some of AFDC’s most punitive behavioral control policies. Lawyers of the Welfare Rights Movement litigated for greater enforcement of federal eligibility standards and won key Supreme Court cases that ended some of the most harmful state eligibility rules discriminating against Black families and precluded states from restricting eligibility.[50] The Supreme Court rulings effectively ended many states’ arbitrary eligibility policies and barred states from adding work or behavioral requirements or eligibility policies that were more restrictive than federal law. The 1960s and 1970s saw dramatic increases in AFDC rolls as more families could access and maintain benefits.

However, the racialized attacks on AFDC and its recipients mentioned above fueled efforts to reverse the federalization of AFDC, leading to the creation of TANF in 1996. In addition to work requirements, states imposed new behavioral requirements under TANF. While some of these policies have since been ended in many states, Southern states often make up the core of states where these policies are still in place:

- Family cap laws deny or limit an increase in cash assistance to families who have another child while enrolled in the program. Similar to earlier reproductive control measures, family caps punish single mothers receiving cash assistance for having additional children. New Jersey Assembly Member Wayne Bryant, who helped pave the way for the country’s first family cap law in 1992, suggested Black women experiencing poverty could not be trusted with cash aid: “If parents are so irresponsible that they are unwilling to come to work or go to school, what makes you think they’re taking the added welfare dollars and spending them responsibly on their kids?” he argued.[51] Between the early 1990s and the early 2000s, 22 states enacted family caps. While half of them (most recently Connecticut) have since repealed their family caps, 11 states — including seven Southern states — still have not.[52]

- In the 1980s, the federal government began restricting certain federal benefits for people convicted of drug-related crimes as part of its War on Drugs, which deeply damaged Black and brown communities.[53] Consistent with that approach, the 1996 law creating TANF barred people with felony drug convictions from receiving TANF benefits. However, the law allowed states to opt out of or modify the policy, and the number of states with a full lifetime TANF ban on people with drug felony convictions dropped from 23 states and D.C. in 1999[54] to seven states today; 26 states and D.C. have lifted the ban entirely.[55] Four of the seven states with full lifetime bans are in the South: Georgia, South Carolina, Texas, and West Virginia.

- While states can require drug tests as a condition of receiving TANF benefits, federal appellate courts have ruled that mandatory “suspicionless” testing is unconstitutional. A number of states have instead enacted suspicion-based drug testing laws. Thirteen states, including seven Southern states, currently have drug testing policies for TANF applicants and recipients.[56] Such policies not only presume participants’ guilt but also invoke racist stereotypes of Black people as criminals and drug users, even though Black and white people use drugs at roughly equal rates.[57] Drug testing policies rarely find people who test positive;[58] instead, they reduce TANF caseloads by creating barriers for applicants.

How Black Women Best Can Help Reimagine Federal TANF Changes

TANF provides little support to families in need — particularly in Southern states, which not only have historically instituted some of the most aggressive policies to exclude and punish Black and other mothers, but also have among the least generous, least accessible TANF programs. TANF programs in nine Southern states have benefits that are less than 20% of the poverty line and reach 10 or fewer families for every 100 in poverty: Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Texas. Four in 10 of the nation’s children who live in poverty, including six in 10 of Black children in poverty, live in the South, and most of those children are concentrated in those nine states with the weakest TANF programs. (See Table 2.) In the South, when parents lose a job or experience some other crisis, they have only limited access to cash supports, potentially exposing them and their children to the consequences of instability.[59]

Cash assistance for families experiencing a crisis needs to be a key component of our economic support system. Currently, TANF is the only source of monthly cash assistance for most families. (While efforts to improve the child tax credit, such as was temporarily done by the American Rescue Plan, are important, it likely won’t be enough for some Black and other mothers with low incomes stemming from discrimination in the labor market, education, and housing.) TANF cash assistance must be fundamentally reimagined through a Black Women Best framework so that Black mothers have a program that provides stability through life’s challenges, protects their children from hardship, and affirms parents’ autonomy over their families and careers. When such a program is available to Black mothers, it will mean that we have crafted a TANF program that works well for all families facing significant economic distress.

As we see with TANF in the South, however, leaving that task up to the states means that many Black children will be left behind. Federal changes are essential to advance racial equity nationally and ensure a stable economic foundation for all families. Federal policymakers should reimagine TANF by doing the following:

- Establishing a federal minimum benefit so that no family of any race falls below a certain income level. A minimum federal benefit would establish a necessary floor to mitigate the large state-by-state disparities in TANF benefit levels and better protect Black, brown, and white families.

- Barring states’ mandatory work requirements. Conditioning benefits on participation in mandatory work programs is one of TANF’s most racially driven policies, one that started with enslavement and continued with coerced labor practices that continued long beyond emancipation. Federal policymakers should eliminate federal requirements that states take away benefits when adults don’t meet a work requirement. Federal policymakers also should bar states from imposing their own sanctions for nonparticipation in work activities.

- Barring behavioral requirements, time limits, and other eligibility exclusions. Rooted in racism and sexism, these provisions demean families by assuming that adults are irresponsible and do not want what is best for their families.

- Refocusing TANF agencies on helping families address immediate crises and improving long-term well-being. Eliminating mandatory work requirements would free up resources within TANF that could be used to help families resolve crises and set and achieve long-term career, personal, and family goals. The families TANF serves (and those who are eligible but not receiving assistance because of restrictive policies) have diverse needs. TANF has an important role to play in helping families access resources within their communities that can help them improve their circumstances and in providing supports that will increase their chances of success.

- Changing TANF’s funding structure to retarget TANF resources to basic assistance, address funding inequities, and prevent erosion over time. States have used TANF resources to pay for other things beside cash aid to families. Federal policymakers should require states to spend a greater share of TANF resources on basic assistance and should also establish an equitable formula for allocating funds among states. (The current formula, based on state spending under AFDC, locked in low funding levels for states where Black children disproportionately live.) Federal policymakers also should increase TANF funds and index them to inflation to encourage states, especially those with lower benefits and higher Black populations, to increase benefits and serve more families.

Remaking cash

assistance requires undoing the consequences — and power — of racist ideas and

policies that have marginalized mothers and their families, Black families especially.

A cash assistance program that centers equity for Black women would, as the

Black Women Best framework posits, promote the economic security of all

families with the lowest incomes.

Citations

[1] Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health, “Turn Away Study,” Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health, University of California San Francisco, https://www.ansirh.org/sites/default/files/publications/files/turnaway_study_brief_web.pdf.

[2] This reflects the abortion policy as of August 25, 2022. More states are likely to ban or severely restrict abortion in the coming months. For a regularly updated overview of states, see Guttmacher Institute, “Interactive Map: US Abortion Policies and Access After Roe,” updated August 25, 2022, https://states.guttmacher.org/policies/indiana/abortion-policies.

[3] Sister

Song: Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective, “Reproductive Justice,”

https://www.sistersong.net/reproductive-justice/.

[1] Carrie Masten, Joan Lombardi, and Philip Fisher, “Helping Families Meet Basic Needs Enables Parents to Promote Children’s Healthy Growth, Development,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and RAPID-EC Survey Project, October 28, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/helping-families-meet-basic-needs-enables-parents-to-promote.

[2] National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, “The Consequences of Child Poverty,” in A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty, 2019, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547371/.

[3] Lucy A. Williams, “Race, Rat Bites and Unfit Mothers: How Media Discourse Informs Welfare Legislation Debate,” Fordham Urban Law Journal, Vol. 22, No. 4, 1995, https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1440&context=ulj.

[4] Danilo Trisi and Matt Saenz, “Deep Poverty among Children Rose in TANF’s First Decade, Then Fell as Other Programs Strengthened,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 27, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/deep-poverty-among-children-rose-in-tanfs-first-decade-then-fell-as.

[5] Ife Floyd, Ladonna Pavetti, Laura Meyer, Ali Zane, Liz Schott, Evelyn Bellew, and Abigail Magnus, “TANF Policies Reflect Racist Legacy of Cash Assistance,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 4, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/tanf-policies-reflect-racist-legacy-of-cash-assistance.

[6] Kendra Bozarth, Grace Western, and Janelle Jones, “Black Women Best: The Framework We Need for an Equitable Economy,” Roosevelt Institute and Groundwork Collaborative, September 2020, https://rooseveltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/RI_Black-Women-Best_IssueBrief-202009.pdf.

[7] Authors’ analysis of 2019 U.S. Census Bureau data. The Southern region includes Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Alexandra Cawthorne Gaines, Bradley Hardy, and Justin Schweitzer, “How Weak Safety Net Policies Exacerbate Regional and Racial Inequality,” Center for American Progress, September 22, 2021, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/poverty/reports/2021/09/22/503274/weak-safety-net-policies-exacerbate-regional-racial-inequality/.

[10] Ira Katznelson, “Jim Crow Congress,” in Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time, Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2013, pp. 156–194; Jill Quadagno, “The Repression of Rights,” in The Color of Welfare: How Racism Undermined the War on Poverty, Oxford University Press, 1994, pp. 20–24.

[11] Floyd et al.

[12] Winifred Bell, Aid to Dependent Children, Columbia University Press, 1965, pp. 34–35.

[13] Ibid., p. 225.

[14] Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia. (See Bell, p. 225.) Analysis of 1960 U.S. Census data, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1960/pc-s1-supplementary-reports/pc-s1-52.pdf.

[15] National Research Council, “The Poverty Measure and AFDC,” in Measuring Poverty: A New Approach, 1995, p. 339, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/1995/demo/afdc.pdf.

[16] Table 5.6 in Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Department of Health and Human Services, “Eligibility, Benefits and Disposable Income,” in Aid to Families with Dependent Children: The Baseline, 1998, https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/167036/5benefits.pdf.

[17] Larry L. Orr, “Income Transfers as a Public Good: An Application to AFDC,” American Economic Review, Vol. 66, No. 3, 1976, pp. 359–371, http://www.jstor.com/stable/1828169; Gerald C. Wright, Jr., “Racism and Welfare Policy in America,” Social Science Quarterly, Vol. 57, No. 4, New Perspectives on Black America, 1970, pp. 718–730, http://www.jstor.com/stable/42859699; Christopher Howard, “The American Welfare State, or States?,” Political Research Quarterly, Vol. 52, No. 2, 1999, pp. 421–442, https://www.jstor.org/stable/449226; Ben Lennox Kali and Marc Dixon, “The Uneven Patterning of Welfare Benefits at the Twilight of AFDC: Assessing the Influence of Institutions, Race, and Citizen Preferences,” Sociological Quarterly, Vol. 52, No. 3, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2011.01211.x.

[18] Kali and Dixon.

[19] Heather Hahn, Laudan Y. Aron, Cary Lou, Eleanor Pratt, and Adaeze Okoli, “Why Does Cash Welfare Depend on Where You Live?” Urban Institute, June 5, 2017, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/why-does-cash-welfare-depend-where-you-live.

[20] Ali Zane and Cindy Reyes, “States Must Continue Recent Momentum to Further Improve TANF Benefit Levels,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 2, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/states-must-continue-recent-momentum-to-further-improve-tanf-benefit.

[21] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and National Diaper Bank Network, “End Diaper Need and Period Poverty: Families Need Cash Assistance to Meet Basic Needs,” September 27, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/end-diaper-need-and-period-poverty-families-need-cash-assistance-to.

[22] Zane and Reyes.

[23] Bell, p. 46; Minoff.

[24] Ibid., pp. 81–83.

[25] Floyd et al.

[26] Martin Gilens, “How the Poor Became Black: The Racialization of American Poverty in the Mass Media,” in Sanford F. Schram, Joe Soss, and Richard C. Fording (eds.), Race and the Politics of Welfare Reform, The University of Michigan Press, 2003, p. 104, https://www.press.umich.edu/pdf/9780472068319-ch4.pdf; Williams.

[27] Quadagno, p. 130.

[28] Paul Gorski, “The Myth of the Culture of Poverty,” in On Poverty and Learning, https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/the-myth-of-the-culture-of-poverty; Premilla Nadasen, Jennifer Mittelstadt, and Marisa Chappell, Welfare in the United States: A History with Documents, 1935-1996, Routledge, 2009, p. 70-71.

[29] Andrew Glass, “Clinton Signs ‘Welfare to Work’ Bill, Aug. 22, 1996,” Politico, August 22, 2018, https://www.politico.com/story/2018/08/22/clinton-signs-welfare-to-work-bill-aug-22-1996-790321.

[30] Aditi Shrivastava and Gina Azito Thompson, “TANF Cash Assistance Should Reach Millions More Families to Lessen Hardship,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated February 18, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/cash-assistance-should-reach-millions-more-families-to-lessen.

[31] Ali Zane, “Maine Joins Growing List of States Repealing TANF Full-Family Sanctions,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 17, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/maine-joins-growing-list-of-states-repealing-tanf-full-family-sanctions.

[32] Carolyn Bourdeaux and Lakshmi Pandey, “Report on the Outcomes and Characteristics of TANF Leavers,” Center for State and Local Finance, Georgia State University Andrew Young School, March 15, 2017, https://cslf.gsu.edu/download/outcomes-and-characteristics-of-tanf-leavers/?wpdmdl=6494571&refresh=5f7852f89a8bc1601721080. See also Ali Zane and LaDonna Pavetti, “Most Parents Leaving TANF Work, But in Low-Paying, Unstable Jobs, Recent Studies Find,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 19, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/most-parents-leaving-tanf-work-but-in-low-paying-unstable-jobs-recent.

[33] Kristin F. Butcher and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, “Most Workers in Low-Wage Labor Market Work Substantial Hours, in Volatile Jobs,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 24, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/most-workers-in-low-wage-labor-market-work-substantial-hours-in.

[34] Bourdeaux and Pandey.

[35] Fred Brooks, Anna Elizabeth Chaney, and Sara Elizabeth Mack, “Georgia’s TANF Leavers 2009–15: How Are They Faring?” Center for State and Local Finance, Georgia State University Andrew Young School of Policy Studies, February 13, 2018, https://cslf.gsu.edu/download/georgias-tanf-leavers-2009-15-how-are-they-faring/?wpdmdl=6494562&ind=1526058317130.

[36] Dorothy Roberts, Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty, Vintage Books, 1997, pp. 22–56.

[37] Ruth Thompson-Miller and Leslie H. Picca, “‘There Were Rapes!’: Sexual Assaults of African American Women and Children in Jim Crow,” Violence Against Women, July 3, 2016, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1077801216654016.

[38] Soraya Nadia McDonald, “‘The Rape of Recy Taylor’ Explores the Little-Known Terror Campaign against Black Women,” The Undefeated, December 14, 2017, https://theundefeated.com/features/the-rape-of-recy-taylor-explores-the-little-known-terror-campaign-against-black-women/.

[39] Many Black widows were not able to access the survivor benefits as the program did not cover agricultural and domestic jobs, industries that included a majority of Black workers at that time. The program extended coverage to these workers and their families in 1954. See James E. Marquis, “Old-Age and Survivors Insurance: Coverage under the 1954 Amendments,” Social Security Bulletin, January 1955, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v18n1/v18n1p3.pdf.

[40] Bell, p. 95.

[41] Ibid., pp. 105, 124–126.

[42] Ibid., pp. 126–131.

[43] Taryn Lindhorst and Leslie Leighninger, “‘Ending Welfare as We Know It’ in 1960: Louisiana’s Suitable Home Law,” Social Service Review, December 2003, pp. 568–569.

[44] Bell, pp. 85–86.

[45] Martha Davis, Brutal Need: Lawyers and the Welfare Rights Movement, 1960–1973, Yale University Press, 1993, p. 64.

[46] Localities included Baltimore, Chicago, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Denver, Detroit, the District of Columbia, Houston, Indianapolis, Kansas City, Los Angeles, Milwaukee, New Orleans, New York City, Oakland, St. Louis, San Francisco, and Seattle. States included Arizona, Connecticut, Illinois, Louisiana, Maine, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Washington. Premilla Nadasen, Welfare Warriors: The Welfare Rights Movement in the United States, Routledge, 2005, p. 6; Bell, pp. 86, 215–216. Also see Bureau of the Census, “Negro Population by County,” U.S. Department of Commerce, March 1966, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1960/pc-s1-supplementary-reports/pc-s1-52.pdf.

[47] Roberts, p. 94; Julius Paul, “The Return of Punitive Sterilization Proposals: Current Attacks on Illegitimacy and the AFDC Program,” Law & Society Review, Vol. 3, No. 1, August 1968, p. 89, https://doi.org/10.2307/3052796.

[48] Roberts, p. 94

[49] Lisa Ko, “Unwanted Sterilization and Eugenics Programs in the United States,” PBS, January 29, 2016, https://www.pbs.org/independentlens/blog/unwanted-sterilization-and-eugenics-programs-in-the-united-states/; Roberts, p. 92.

[50] The court’s 1968 ruling in King v. Smith, for example, struck down Alabama’s “substitute father” policy and eliminated other “man in the house” rules; it also barred states from instituting additional eligibility rules, thereby shifting the power to determine eligibility restrictions from the states to the federal government. And in Goldberg v. Kelly (1970), the court ruled that AFDC recipients had a right to a hearing before their benefits were terminated, among other due process measures.

[51] Wayne R. Bryant, “New Jersey’s Welfare Overhaul,” Washington Post, October 1, 1995, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/1995/10/01/new-jerseys-welfare-overhaul/5ed21817-4d83-47ae-950e-4c83473266fa/.

[52] Ife Floyd, “States Should Follow New Jersey: Repeal Racist ‘Family Cap,’” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 14, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/states-should-follow-new-jersey-repeal-racist-family-cap. Connecticut repealed its law in 2021.

[53] David H. Carpenter, “Constitutional Analysis of Suspicionless Drug Testing Requirements for the Receipt of Governmental Benefits,” Congressional Research Service, March 6, 2015, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42326.pdf.

[54] See Appendix A in Amy Hirsch, “‘Some Days Are Harder Than Hard’: Welfare Reform and Women with Drug Convictions in Pennsylvania,” https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/public/resources-and-publications/files/0167.pdf, p. 79. The appendix includes the 27 states with full bans and modified bans.

[55] Darrel Thompson and Ashley Burnside, “No More Double Punishment: Lifting the Ban on SNAP and TANF for People with Prior Drug Felony Convictions,” Center for Law and Social Policy, April 19, 2022, https://www.clasp.org/publications/report/brief/no-more-double-punishments/. Colorado fully lifted the drug felony ban in June 2022.

[56] Darrel Thompson, “Drug Testing and Public Assistance,” Center for Law and Social Policy, February 5, 2019, https://www.clasp.org/publications/fact-sheet/drug-testing-and-public-assistance. Since this report’s release, Maine has repealed its drug testing requirement and West Virginia has turned its drug testing pilot into a full program.

[57] National Center for Health Statistics, “Health, United States, 2019,” 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2019/020-508.pdf.

[58] Amanda Michelle Gomez and Josh Israel, “What 13 States Discovered after Spending Hundreds of Thousands Drug Testing the Poor,” ThinkProgress, April 26, 2019, https://archive.thinkprogress.org/states-cost-drug-screening-testing-tanf-applicants-welfare-2018-results-data-0fe9649fa0f8/.

[59] Harvard University Center on the Developing Child, “Connecting the Brain to the Rest of the Body,” https://46y5eh11fhgw3ve3ytpwxt9r-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/InBrief-Connecting-the-Brain-to-the-Rest-of-the-Body.pdf.

Downloads

- turnaway study brief web

- RI Black Women Best IssueBrief 202009

- https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1960/pc-s1-supplementary-reports/pc-s1-52.pdf

- https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/1995/demo/afdc.pdf

- https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/167036/5benefits.pdf

- https://www.press.umich.edu/pdf/9780472068319-ch4.pdf

- https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v18n1/v18n1p3.pdf

- https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42326.pdf

- https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/public/resources-and-publications/files/0167.pdf

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2019/020-508.pdf

- InBrief Connecting the Brain to the Rest of the Body